The iNaturalist community made international headlines a few weeks ago after the first hoodwinker sunfish (Mola tecta) seen in North America was shared and then identified via iNaturalist and some dedicated participants. It really is a great story that shows the power of collaboration and the importance of keeping an open (and optimistic!) mind, so I thought it would be fun to compile an oral (although in this case, written) history from the participants.

What follows are the lightly edited and condensed recollections of most of the people involved, put together as chronologically as possible. I have not heard back from all participants, but am happy to add your input if you message me.

Jessica Nielsen (Coal Oil Point Reserve): My first observation of the hoodwinker sunfish was on the morning of February 19th, 2019. A colleague, Mark Holmgren, and I were conducting the reserve's monthly bird monitoring survey at around 7:00 am and noticed a tall dorsal fin flopping about in the water about a hundred meters off of the point at Coal Oil Point Reserve. We weren't sure at the time what animal we were looking at as we couldn't see it very clearly in the water, but we assumed it was some kind of marine mammal based on the size of the fin and head. Later the same day, when a 7 foot long sunfish washed up on the beach, we realized that was what we had seen that morning.

I was alerted to the washed up fish by one of our UCSB student interns, Ruth Alcantara... Unfortunately, the fish was already dead but it was still a sight to see such a large and unusual fish up close. I took some measurements and photos and posted the finding to Coal Oil Point Reserve’s Facebook page.

Daniel Spach (Wilderness Youth Project): We were about to leave Devereux that day after tidepooling for a couple hours when a couple of the kids spotted what looked like a dead seal or something in an unusual posture near the beach on the rocks. When we got over there we were stunned to find something I had never seen or heard of anyone finding on a Santa Barbara beach... a Sun Fish? It was longer than I am tall, over 7 feet I'd say, super flat and roundish, with a mouth big enough to swallow my head. All the kids gathered round and were giddily excited about it, noting the shape of the fins and eyes, making guesses as to its watery demise. Everyone seemed a bit scared to touch it though, thinking it would be slimy like most decomposing fish we'd encountered but its skin was actually extremely hard, dense, and rough, like an ocean rhino or something.

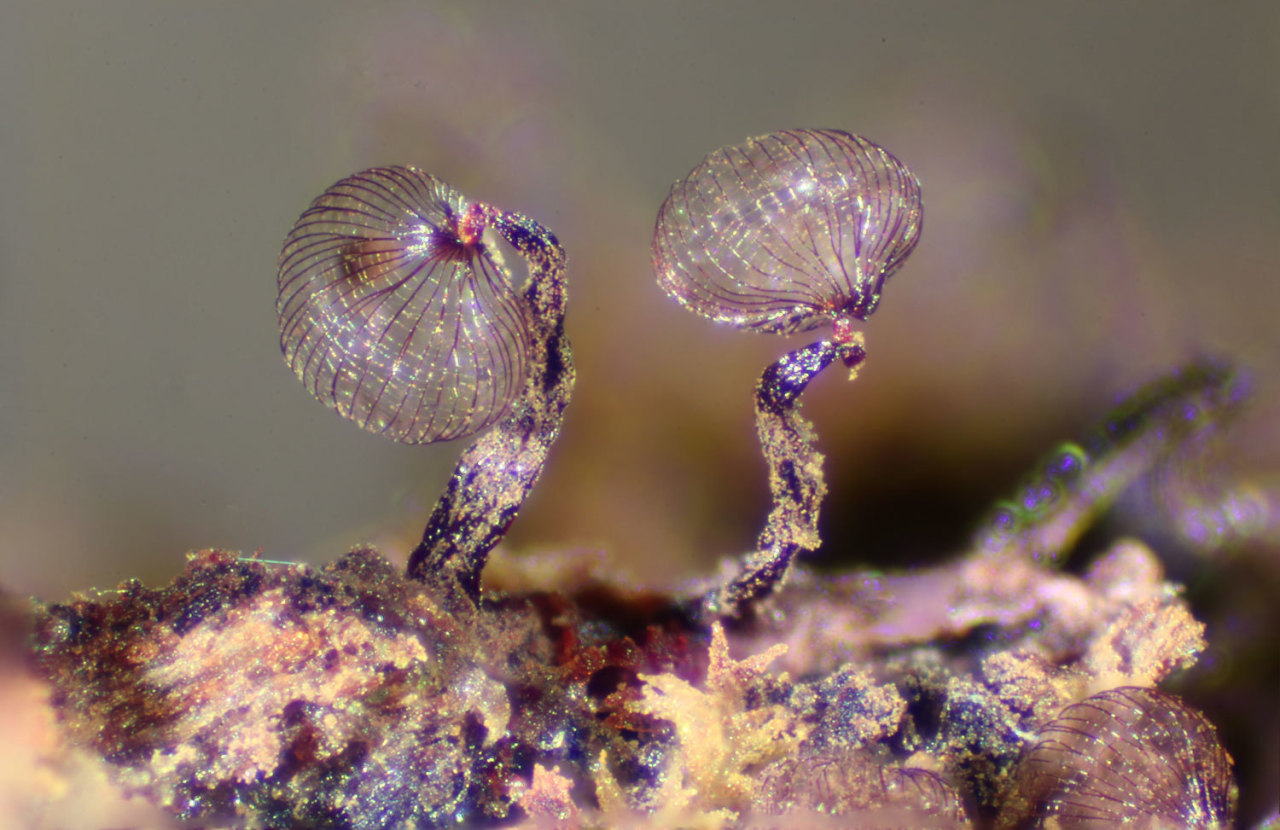

Kittyhawk snapped a few pictures [TI: see above] with her phone. The kids all wanted to make sure their parents would get a copy of the pictures. Might be the only time any of us will encounter this fish for our lifetimes.

Jeff Phillips (@ljefe): My 10-year old son Pierce participates in the Wilderness Youth Project’s after school program every Wednesday. [On] Feb 22, when I met the group to pick up my son and friends at 5:30pm, they were excited about this huge fish they had found on the beach during their afternoon outing (sometime between 2 and 4:30pm). I’m a biologist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service so they knew I’d be excited about it. I had them send me the photo and with my son’s help to mark the location, I posted it on iNaturalist, originally identifying it as Mola mola. I thoroughly enjoyed the ensuing discussion among tomleeturner, rfoster, and mnyegaard.

Tom Turner (@tomleeturner): I saw [Jessica’s] post and went down there with my family, because I wanted my 4 year old son to check it out. I posted it on iNat, of course, because…that is what I do. Everyone was assuming it is a Mola mola. What happened next is a classic example of iNat at its best.

Ralph Foster (@rfoster): I have an alert for Mola spp and was checking through the day's offerings when I saw what I took to be a stranded Mola tecta. I was bewildered when I realised this was in California and not in New Zealand or Australia so I tagged Marianne [Nyegaard, who described Mola tecta], asking for her input.

Marianne Nyegaard (@mnyegaard): Ralph Foster emailed me with links to iNaturalist asking if I could see what species it was, strongly suspecting it was Mola tecta. I quickly checked and thought that the fish surely looked like a hoodwinker, but frustratingly, none of the many photos showed the clavus [TI: aka what sunfishes’ back “fin” is called] clearly. And with a fish so far out of range, I was extremely reluctant to call it a hoodwinker without clear and unambiguous evidence of its identity... I emailed Ralph and told him we needed more photographs and ideally a tissue sample, and posted on iNaturalist that his was probably just a Mola mola.

Ralph Foster: Since there were no diagnostic features shown, I also tagged the observer (@sealovelife) asking if there were more images available, which is when Tom directed me to his observation.

Tom Turner: By this time I was already out on the beach in the dark looking for the fish to get better photos, because what could be more fun than this? Alas, the tide had floated it away again.

Marianne Nyegaard: I then had a cup of coffee and doubt starting creeping in... I spent the next few hours obsessively zooming in on all the photos posted on iNaturalist... Some photos showed peoples’ hands on the sunfish, so I used their fingernails to gauge the scale and compared the skin with my archive photos. Even though the resolution just wasn't high enough to be sure, I started convincing myself the skin at least wasn't incompatible with Mola tecta and that ….perhaps it was a hoodwinker?... But I felt I needed to be absolutely 100% sure before settling on an ID, seeing I had described the hoodwinker and would need to back up my ID with absolute certainty with a specimen so far away from home.

I woke up to an email from Jessica Nielsen saying [she and Tom] were keen to go back out and find the fish again so I sent them instructions of what to look for and photograph, and then sat on the edge of my chair with all fingers and toes crossed that they would find it.

Tom Turner: At low tide (now two days later), I started biking on the beach from the east, and Jessica started walking from the west, 2 miles apart. We met in the middle, at the fish, now a few hundred yards farther east.

Jessica Nielsen: Tom and I waited for the tide to go out, found the fish...and we got to work taking the photos and fin clips requested. It really was exciting to collect the photos and samples knowing that it could potentially be such an extraordinary sighting! Once we sent over the photos, Marianne responded very quickly.

Marianne Nyegaard: I was away from my desk most of the day, but when I checked my emails in the afternoon I literally nearly fell off my chair (which I was sitting on the edge of!). Tom and Jessica had indeed found the fish and had photographed and examined it, and taken a tissue sample. A huge amount of extremely clear photos were in my inbox and there was just no doubt of the ID. They had also examined the clavus by hand to confirm the number of ossicles, which was just brilliant. Eyes and ears and hands on the ground half a world away, wow.

Ralph Foster: If it hadn't been for Tom and Jessica's willingness to revisit and examine the specimen we would not have known with certainty that this was, indeed, Mola tecta.

Jessica Nielsen: We were all thrilled to hear the news. Mola tecta was just recently discovered in 2017 (by Marianne and her research team) so there is still so much to learn about this species. I’m so glad that we could help these researchers make the final definitive ID.

Tom Turner: iNaturalist at its best: experienced novice loops in expert who loops in the expert who then helps us learn about our find and gets info she will use in her research. And it was fun and exciting for all.

Marianne Nyegaard: Ralph Foster also alerted the University of California, who did a beach dissection and collected a large number of samples. Tissue samples will soon be on the way from California to my sister’s lab in Denmark, where I do all my sunfish genetics.

So, within 24 hours after I had first been made aware of this stranding we had confirmed the ID. I just love iNaturalist and am continuously amazed by how much fun it is to “meet” passionate people all over the world