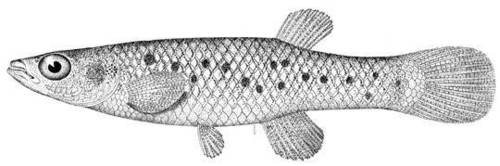

Saltmarsh topminnow

Fundulus jenkinsiProfile / Morphology 2

Saltmarsh topminnows have a guppy-like body shape and fin positions. They have little color, but there is cross-hatching on the back and sides that may be gray-green or fainter. Saltmarsh topminnows often have 12 to 30 dark round spots arranged in rows along the midside of the body, from above the pectoral fin to the base of the caudal (tail) fin. There is little difference between the sexes other than longer median fin length in males, a lemon-yellow color that develops on male anal fins, and a sheath found on the anterior base of the anal fin of mature females. This sheath is used to help position eggs during spawning (Thompson 1980, 1999).

Diet 2

There is no specific diet information on the species, but they are likely to eat small invertebrates.

Size / Weight 2

The saltmarsh topminnow is one of the smallest members of the topminnow/killifish family (Fundulidae). It seldom exceeds 1.75 inches (40-45 mm) in length, with most individuals in scientific collections ranging from 1 to 1.4 inches (25 to 35 mm). Females become larger than males by a quarter to one-half of an inch or so. They weigh an ounce or so.

Habitat 2

Saltmarsh topminnows live in estuaries, coastal salt marshes and back water sloughs, including shallow tidal meanders of Spartina cordgrass marshes. They are tolerant to salinities of 1 to 20 parts per thousand (Thompson 1999). Abundance is highest in Spartina cordgrass and Juncus rush salt marshes with salinity of 1 to 4 parts per thousand in small, shallow tidal meanders (Thompson 1980).

Peterson and Turner (1994) used a variety of net types and positions to determine that saltmarsh topminnows belonged to the group of species that use the edge (rather than the interior) of a Louisiana saltmarsh, adjacent to a tidal creek. This was in contrast to other relative species (called cyprinodontids) that used the marsh interior more. Rozas and Minello (2006) found that saltmarsh topminnows exclusively used marsh edges and were absent from Vallisneria (eelgrass), and nonvegetated areas of Louisiana marshes. From a survey of 82 locations from Biloxi, Mississippi to Mobile, Alabama, abundance was found to be highest at depths of about 1 to 2 feet (0.5 m), salinities of less than 12 parts per thousand, and temperatures over 68°F (20°C) (Peterson et al. 2003).

Range 2

The saltmarsh topminnow is endemic from Galveston Bay, Texas to Escambia Bay in the western panhandle of Florida. Distribution is sporadic across the range.

Reproductive / Life Span 2

Breeding occurs from March to August in shallow flooded marshes. Unlike most fish which broadcast spawn sperm or eggs into the water column or lay eggs on the bottom, saltmarsh topminnows belong to a group that has internal fertilization. Males use an elongate contact organ structure on their anal fin to inseminate females. The smallest male having the reproductive contact organs on the anal fin rays and lateral body scales was 21 mm (Thompson 1999). There are no data on how many eggs are produced or reproductive behavior (Thompson 1999). Larvae are seen in May and June and juveniles are first seen in July. Few adults survive beyond breeding in their second year of life.

Relatives 2

Saltmarsh topminnows are part of the killifish, or topminnow family. This includes 46 species of fishes that occur throughout North America and generally live in estuarine conditions. The distinguishing family characteristic is that the maxillary bone (upper jaw) is twisted instead of being straight.

Found in the following Estuarine Reserves 2

Weeks Bay (AL) and Grand Bay (MS)

Water quality factors needed for survival 2

Water Temperature: one study found greatest abundance in areas with temps over 20 and up to 32 °C

Turbidity: tolerate moderate turbidity 1-69 NTU

Water Flow: low

Salinity: tolerate 1 to 25 ppt, most common in 5 to 15 ppt

Dissolved Oxygen: 2- 11 mg/L

Threats 2

Habitat alteration, dredging, and marsh erosion are the most serious threats to the Saltmarsh topminnow. •In the lower Mississippi River delta system, coastal erosion from poor land use practices is decreasing their marsh habitat.

•Erosion of marsh areas on several of Louisiana’s barrier islands has completely eliminated several locations where this species was collected in the past (Thompson 1999).

•The conversion of marsh to deeper, open water from dredging for ship and boat channels, or other human uses eliminates important feeding, sheltering, and breeding areas.

•Dock and other bulk-head construction along marsh edges may prevent saltmarsh topminnows from accessing flooded marsh surfaces (Thompson 1999).

•Hurricanes dating back to at least George (1998) have further reduced available saltmarsh habitat. No assessments have been done since hurricanes Dennis, Katrina, and Rita of 2005.

Conservation notes 2

There are ongoing programs designed to restore coastal marsh to provide habitat for the

Saltmarsh topminnow, but success has not yet been determined. Significant genetic mixing of separated populations is not likely (Poss 1999), so the species genetic diversity is at risk as it becomes more isolated.

Abundance has likely declined with extensive loss of habitat. The species is generally rare and sample sizes are generally small, though they can be locally common (Gilbert and Relyea 1992). They are more common in the central part of their range and in salt marshes dominated by Spartina cordgrass or Juncus rushes. Peterson et al. (2003) document the first records of the species from the Pascagoula River watershed.

Importance to Humans and Estuaries

Due to their small size, saltmarsh topminnows are not of economic value directly. They can have an important place in the food chain, as they can be prey for larger, commercially important species.

How to Help Protect This Species

•Saltmarsh topminnows use estuaries and near freshwater areas. They are susceptible to water pollution, plus damage to and alteration of estuary habitats. Suggested methods to help this species include:

•Minimize runoff of neighborhood pollutants, fertilizer, and sediment into local streams that feed estuaries are helpful to this species, or other stream and estuary dwelling species.

•Join a stream or watershed advocacy group in your area to protect your local estuary ecosystems.

•Advocate the restoration of more natural water flow regimes.

•Advocate greater protections (laws, regulations) to stop the removal of vegetation or dredging of habitat for docks, harbors, and other structures.

•Support conservation programs like the Species of Concern program and other non governmental organization programs.

•Support long-term research and monitoring programs to obtain needed information described below. Further ecology studies would help determine the specific diet and microhabitat needs for the species. Sampling in the far eastern and western parts of the species range has not occurred for decades (Thompson 1999). Post-hurricane sampling in Louisiana and Mississippi would be valuable as would long-term monitoring.

Sources and Credits

- (c) Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of Natural History, Department of Vertebrate Zoology, Division of Fishes, some rights reserved (CC BY-NC-SA), https://collections.nmnh.si.edu/services/media.php?env=fishes&irn=5006520

- (c) GTMResearchReserve, some rights reserved (CC BY-SA)