stinging nettle

Urtica dioicaSummary 7

Urtica dioica, often called common nettle or stinging nettle (although not all plants of this species sting), is a herbaceous perennial flowering plant, native to Europe, Asia, northern Africa, and western North America, and is the best-known member of the nettle genus Urtica. The species is divided into six subspecies, five of which have many hollow stinging hairs called trichomes on the leaves and stems, which act like hypodermic needles, injecting histamine and other chemicals that...

Worldwide distribution 8

In temperate regions of the world

Description 9

More info for the terms: achene, dioecious, epigeal, forb, monoecious

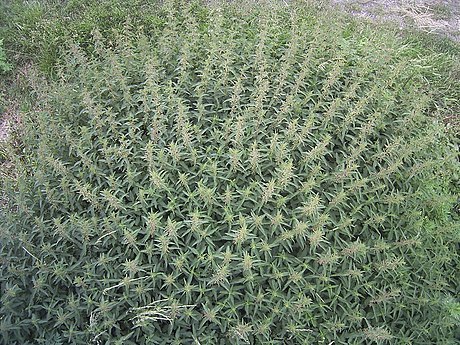

Stinging nettle is an erect, perennial, rhizomatous forb which forms

dense clonal patches. Stout stems grow 3.3 to 6.6 feet (1-2 m) tall.

Leaves, stems, and flowers are sparsely to moderately covered with

stinging hairs. Two subspecies, American stinging nettle and hoary

nettle, are native; the third subspecies in North America, European

stinging nettle, was introduced in the mid-1800's. American stinging

nettle and hoary nettle are predominantly monoecious whereas European

stinging nettle is typically dioecious. The fruit is an achene [1,51].

Stinging nettle has both epigeal and shallow subterranean rhizomes [35].

Key plant community associations 10

More info for the term: marsh

Stinging nettle is a common understory component of riparian communities

[30,50,52]. In the Santa Ana Mountains along the southern California

Coast, American stinging nettle occurs in the understory of a riparian

woodland dominated by California sycamore (Platanus racemosa), white

alder (Alnus rhombifolia), and red willow (Salix laevigata) [48]. In

Kern County, California, hoary nettle is abundant in the understory of a

Fremont cottonwood (Populus fremontii), Pacific willow (Salix

lasiandra), and red willow community [23]. In Montana, American

stinging nettle occurs in a western redcedar (Thuja plicata) community

in a ravine dissected by spring run-off channels [18].

Stinging nettle occurs in and adjacent to marshes and meadows. In North

Dakota, stinging nettle occurs in a sedge (Carex spp.)-dominated zone

between an emergent marsh and upland meadow [29].

Stinging nettle occurs in moist forest communities in the southern

Appalachian Mountains [4].

Broad scale impacts of plant response to fire 11

More info for the term: prescribed fire

Hamilton's Research Papers (Hamilton 2006a, Hamilton 2006b)and Metlen and

others' Research Project Summary provide information on prescribed fire

and postfire response of many plant species including stinging nettle.

National nature serve conservation status 12

Canada

Rounded National Status Rank: N5 - SecureUnited States

Rounded National Status Rank: N5 - SecureThreats 13

This species is not threatened.

Common names 14

stinging nettle

American stinging nettle

European stinging nettle

hoary nettle

Comprehensive description 15

Stinging Nettle

Urtica dioica or stinging nettle is a broadleaf angiosperm and of the Urticaceae family. This perennial typically grows to between 1-3m tall with dark green leaves in an opposite pattern that are oval to heart shaped and saw toothed and are sparsely covered with stinging (and nonstinging) hairs (Schellman and Shrestha 2008). The flowers are green to white in color, with drooping clusters of four petals per flower, and occur in the leaf axils as well as at the stem tips. The fruit of the stinging nettle are small, flattened, lenticular achenes (Pojar and MacKinnon 2004).The native range of Urtica dioica spans Europe, Asia, northern Africa, northern Mexico, and, in Canada and the US, every province and state except Alabama, the District of Columbia, Georgia, North Carolina, Virginia, in all of which it has been introduced, and Hawaii, where it is absent (CABI 2016), and it is typically found in meadows, thickets, and open forests as part of the understory of riparian ecosystems (Pojar and MacKinnon 2004). Stinging nettle thrives in temperate climates, particularly in wet soil that is rich in nitrogen. It prefers full sunlight and is often able to survive in areas where few species can. Generally, stinging nettle does well near rivers or lakes, but it can also be successful in environments subjected to human degradation, or on farm lands because of the rich nitrogen levels in the soils (Carey 1995). Since it grows in abundance in many locations, stinging nettle can be considered a common weed. And although it is native across a wide global range, it is often perceived as invasive due to its irritating and rather prolonged sting (CABI 2016). Stinging nettle germinates in the spring and continues to grow until late fall and individuals and colonies can also continue to regrow for many years due to their rhizome system. Rhizome pieces or parts of stems have the ability to grow into mature plants if proper conditions prevail (Schellman and Shrestha 2008).

Stinging nettle is a food source for many butterflies and aphids and the plentiful seeds provide nourishment for birds as well. Historically, the plant was cultivated for food and other industries in European countries such as Scotland, Denmark and Norway for food and other industries. Young stinging nettle can also be cooked and eaten, since cooking the leaves destroys the sting (Kew 2016; Pojar and MacKinnon, 2004). Stinging nettle has also been used in fabric dye and the tough fibers of the stems have been used for textiles (Schellman and Shrestha 2008).

Stinging nettle is infamous for its painful sting that is caused by toxins from the hairs on the stems and leaves, which apparently evolved in order to keep animals from eating the nutritious plant. These stinging hairs are needle like tubes that can pierce the skin and inject histamine and acetylcholine, which causes burning and itching that can last up to 12 hours. Nettle stings have also been found to have an anti-inflammatory property and can be used for medicinal purposes, and preparations derived from the root are used in treating benign prostate hyperplasia (Kew 2016).

Sources and Credits

- (c) Jacky Judas, some rights reserved (CC BY), uploaded by Jacky Judas

- (c) Franz Xaver, some rights reserved (CC BY-SA), https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/14/Urtica_dioica_1.jpg/460px-Urtica_dioica_1.jpg

- (c) Denis Barthel, some rights reserved (CC BY-SA), https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/90/Urtica_dioica_large_stand.jpg/460px-Urtica_dioica_large_stand.jpg

- (c) Hermann Falkner, some rights reserved (CC BY-NC-SA), http://farm7.static.flickr.com/6149/5923659492_5e99cda1d2.jpg

- (c) Biopix, some rights reserved (CC BY-NC), http://www.biopix.com/PhotosMedium/JCS%20Urtica%20dioica%2027651.jpg

- (c) Huc Marian, some rights reserved (CC BY), https://www.biolib.cz/IMG/GAL/28865.jpg

- (c) Wikipedia, some rights reserved (CC BY-SA), http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Urtica_dioica

- (c) Mark Hyde, Bart Wursten and Petra Ballings, some rights reserved (CC BY-NC), http://eol.org/data_objects/30293011

- Public Domain, http://eol.org/data_objects/24630457

- Public Domain, http://eol.org/data_objects/24630453

- Public Domain, http://eol.org/data_objects/24630465

- (c) NatureServe, some rights reserved (CC BY-NC), http://eol.org/data_objects/29057960

- (c) Wildscreen, some rights reserved (CC BY-NC-SA), http://eol.org/data_objects/6691120

- Public Domain, http://eol.org/data_objects/23368164

- (c) Authors: Brooke Galberth and Colton Cheshier; Editor: Gordon L. Miller, Ph.D.; Seattle University EVST 2100 - Natural History: Theory and Practice, some rights reserved (CC BY), http://eol.org/data_objects/34785087

More Info

- iNat taxon page

- African Plants - a photo guide

- Atlas of Living Australia

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- BOLD Systems BIN search

- Calflora

- CalPhotos

- Catalogo de Plantas y Líquenes de Colombia

- eFloras.org

- Flora Digital de Portugal

- Flora of North America (beta)

- Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF)

- Go Botany

- HOSTS - a Database of the World's Lepidopteran Hostplants

- infoflora

- IPNI (with links to POWO, WFO, and BHL)

- Jepson eFlora

- Maryland Biodiversity Project

- NatureServe Explorer 2.0

- NBN Atlas

- New Zealand Plant Conservation Network

- SEINet Symbiota portals

- Tropicos

- USDA PLANTS database

- VASCAN by Canadensys

- World Flora Online

- 日本のレッドデータ検索システム

- 植物和名−学名インデックス YList