I came across this article in January and thought the study was a great example of how iNaturalist data can be used for research, so I reached out to researcher Michael Moore (@moore-evo-eco) about it. He was gracious enough to spend some of his time to answer my questions. Thank you Michael!

Michael Moore, a graduate biology student at Case Western Reserve University in Ohio, says he’s been studying blue dasher dragonflies for his research over the course of a few years, pretty much because they’re common across much of the middle of North America. Before he had even done field research with this species, Michael heard that males in the eastern part of the continent had darker wings than those on the western side. “I kind of filed that anecdote away in the back of my brain while I used the species for research in other topics,” he recalls. “But in the winter of 2016-2017, while I waited for the snow to clear so I could get back out there and do some research, I realized that the reason this dragonfly species has different wing color patterns in different parts of North America might be really interesting and worth investigating.”

Blue dashers would not be flying until the weather warmed, but Michael was chomping at the bit to get started with his research so he turned to iNat. “When I went to check the iNaturalist page for blue dashers, I could not believe how many really, really high-quality pictures there were just of this one species I happen to research,” he tells me. “I think at this point there are like 13,500 observations--so trove is definitely the right word...

Once I started looking through these pictures, I realized that the information that iNaturalist stores was literally everything I needed not just to get some preliminary data, but to decisively address where the dragonfly tended to get the color on its wings and where it did not....After seeing that pattern from the iNaturalist photos, there was no question that I was on to something. I applied for a bunch of small grants for experiments on how I would follow up on this exciting geographic pattern, and I got enough funding from the American Museum of Natural History and my department that I could do the experiments. Without the amazing collection of pictures of just this one little dragonfly on iNaturalist, I'm not sure any of the rest of this research would have been possible.

After getting range and wing coloration data from iNaturalist, Michael and his colleagues obtained male specimens and tested how wing coloration affected the dragonflies’ body temperatures; whether or not a higher body temperature translated into better flight performance; how wing coloration and weather affected a male’s ability to defend territory; and finally, whether wing coloration was reduced in hotter parts of the species’ range (using iNaturalist observations). What they found was that increased body temperature did improve flight performance - up to a point. Once the dragonfly’s body temperature was too high, flight performance was negatively impacted, thus reducing the male’s ability to defend territory and in turn mate with a female. So the reduced wing coloration in hotter areas of the blue dasher’s range does correlate with sexual selection and fitness.

“For me at least, the first big benefit of the data available from iNaturalist is the sheer volume of high-quality observations that are available for some species. It's still hard for me to get my head around,” says Michael. “While gathering natural-history observations is a key element of biological research, it would take years for a small team of researchers to collect that many observations. This can really jumpstart the process of identifying patterns and figuring out which ones are worth designing experiments to understand at a deeper level.” He does acknowledge that he lucked out with blue dashers because they are a charismatic, commonly observed species, and he also wishes that the photos were more standardized, so he says “I suspect that plants and animals that don't catch people's eye quite as much might not be as amenable to these kinds of studies. But these are small drawbacks when compared to the really amazing opportunities that platforms like iNaturalist present...

as more and more researchers start working with these great platforms, I really think we could witness an explosion of newly uncovered patterns in global biodiversity. The key then will obviously be to design careful follow-up experiments to help us understand why these patterns arise in the first place, but the possibilities that iNaturalist and eBird present as a jumping off point are remarkable…

...Because we are now accumulating this remarkable collection of time-stamped photographs of every manner of plant, animal, and fungi through iNaturalist and similar platforms, we're potentially going to have a digitized record of how each of these organisms evolve over the next few decades. We'll be able to watch evolution occurring on a grand scale. From a purely academic perspective, it's every evolutionary biologists dream.

What’s next for Michael? He has some ideas about how iNaturalist and other crowdsourced data can be used, but he’s also interested in following up on this dragonfly study. “Like many research projects, there are a lot more questions that this study raises than answers,” he says. “Did the dragonflies evolve to have reduced wing coloration in the hotter areas, or vice versa? What about areas where they don’t have much wing coloration yet the temperatures are not as hot?

“Identifying the evolutionary forces that act in addition to temperature to cause these patterns will hopefully help biologists understand how animals adapt to simultaneously balance the competing demands of multiple environmental factors,” Michael concludes. “Without that initial boost from the iNaturalist dataset, I probably never would have looked seriously at the role of temperature in the evolution of this trait, and we would have had no idea that we could use this species to examine these all of these important evolutionary ideas and concepts”

By Tony Iwane

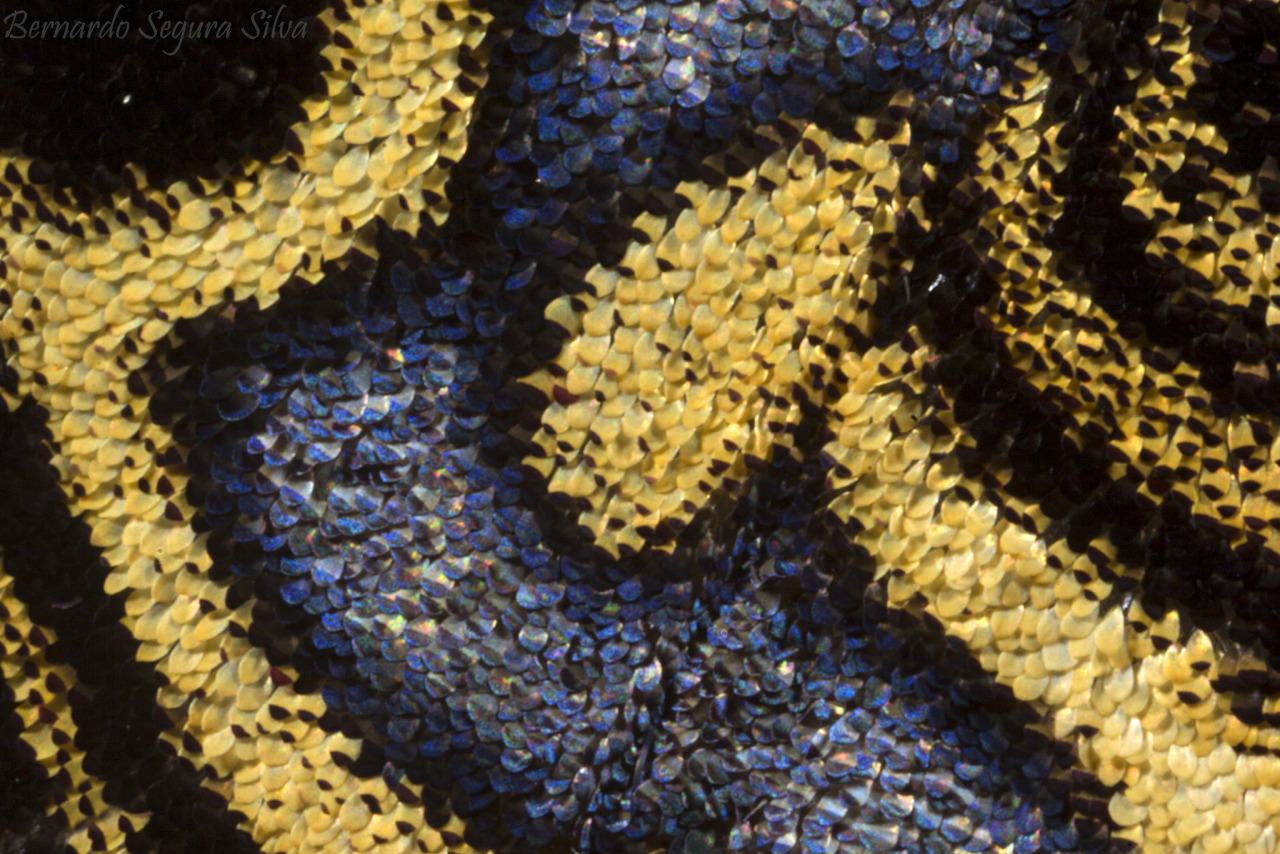

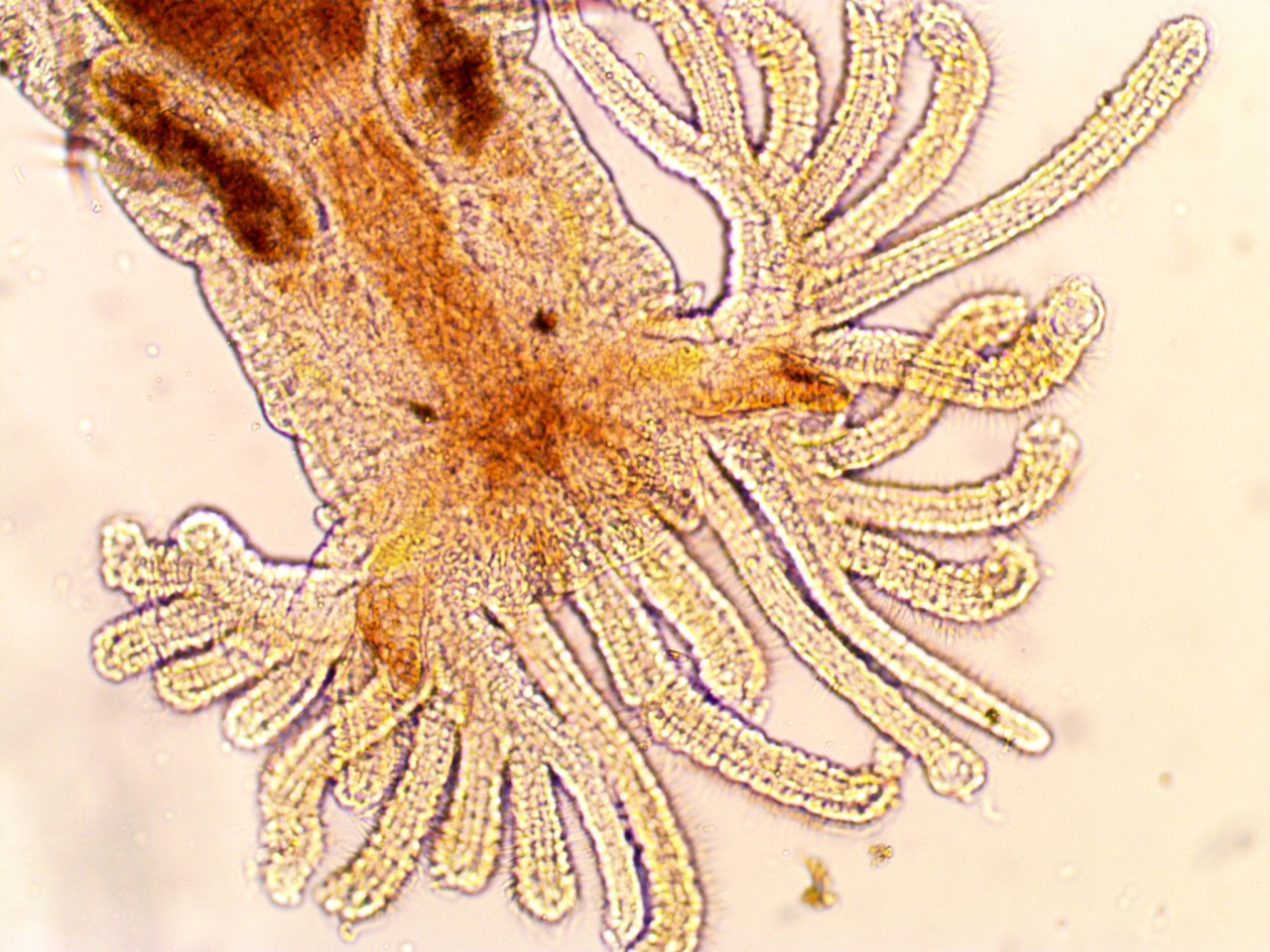

Photos: Male blue dasher in Ohio by Dave McShaffrey (top); Male blue dasher in Arizona by Alex Lamoreaux (middle).

- This study is under embargo for a year, but an abstract can be found here. Michael’s co-authors were Cassandra Lis, Iulian Gherghel, and Ryan A. Martin.

- Check out another ongoing study that’s using iNat photos of mountain goats.

- A blue dasher photo was chosen as an iNat Observation of the Day. However, its in the jaws of a snake! Great photos.