Johnson's Seagrass

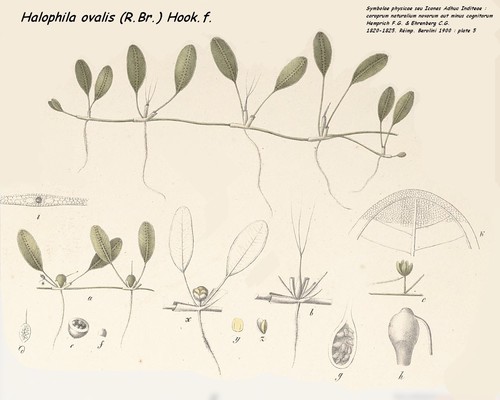

Halophila ovalisProfile / Morphology 4

Like all other seagrasses, Johnson’s seagrass is clonal, which refers to plants that have many semi-independent units (ramets) acting together as a single organism. It is a perennial plant species that shows some decline in winter. Identifying characteristics of Johnson's seagrass include smooth margins, spatulate leaves in pairs 1 to 2 inches (2.5 to 5 cm) long, a creeping rhizome (a horizontal subterranean plant stem like the runners on a Strawberry plant) with stalks attached to the leaves, sessile (attached to their bases) female flowers, and longnecked fruits. The male flowers are unknown. Outstanding differences between Johnson's seagrass and other similar species are its distinct asexual reproduction, and leaf shape and form.

Diet 5

Johnson’s seagrass is a photosynthetic plant, which can acquire nutrients from the sediment, or the water column.

Average lifespan in the wild 5

Leaf pairs can live weeks or months, but the entire clonal organism can live much longer

Size / Weight 5

Individual leaf pairs are 1 to 2 inches (2 to 5 cm) in length. Patches or meadows of this seagrass can be up to 30 acres in size / not applicable

Habitat 5

Johnson's seagrass prefers to grow in coastal lagoons in the intertidal zone, or deeper than many other seagrasses. It does worse in the intermediate areas where other seagrasses thrive. The species has been found in coarse sand, muddy substrates, in areas of turbid waters and high tidal currents, as well as near freshwater discharge canals. Widely spaced patches, usually on the order of 1-20 square meters in size, are the most commonly encountered feature of Johnson’s seagrass meadows (Virnstein et al. 1997). Johnson’s seagrass is more tolerant of salinity, temperature, and desiccation variation than other seagrass species in the area, and therefore, can occur further into estuaries.

Range 5

Johnson's seagrass is only found in southeastern Florida from Sebastian Inlet to Biscayne Bay. The largest patches have been documented inside Lake Worth Inlet, and are about 30 acres (Kenworthy, 1997). Ten areas of critical habitat have been defined under the Endangered Species Act (Figure 2).

Reproductive / Life span 5

The species is only known to reproduce asexually, and may be limited in distribution because of this characteristic.

Individual leaf pairs can live weeks or months, but the entire clonal organism can live much longer.

Relatives 5

Johnson’s seagrass is in the family Hydrocharitaceae, the tape grasses, that includes many aquatic plants living in fresh and salt water worldwide, but mostly in the tropics. Some well known relatives include the widespread waterweed Elodea, Hydrilla, turtle grasses, and eelgrasses (Vallisneria).

Found in the following Estuarine Reserves 5

none

Water quality factors needed for survival 5

•Water Temperature: can survive intertidally, tolerates 10 to 30 °C

•Turbidity: low to high

•Water Flow: 0 – 0.4 m/s

•Salinity: maximum growth and survival at 30 ppt, tolerates 15 to 35 ppt

•Dissolved Oxygen: tolerates low oxygen

Threats 5

Continued existence and recovery of Johnson’s seagrass may be limited due to habitat alteration by a number of human and natural perturbations. Such perturbations include (1)habitat alteration and loss, by propeller scarring, (2) dredging, (3) storm action, (4) sedimentation , (5) degraded water quality and (6) construction practices. These threats are described in detail below. 1.Habitat alteration and loss: Johnson’s seagrass is a shallow rooted species and vulnerable to uprooting by wind waves, storm events, tidal currents, bioturbation, and motor vessels. Alteration and subsequent destruction of the benthic community from boating activities, propeller scarring of the substrate, anchoring, and mooring of boats has been observed in Johnson's seagrass sites. Such activities result in broken root systems, severed rhizomes, and significant reductions of the physical stability of the substrate.

2.Dredging: Dredging waterways for boat access redistributes sediments, buries plants and destroys bottom topography.

3.Storm action: Erosional forces and sedimentation associated with severe storms are likely to affect some abundant populations located near inlets. During hurricanes, storm surge may scour and redistribute sediments, thereby eroding or burying existing populations.

4.Siltation: siltation due to human disturbance and land-use practices can also threaten species viability.

5.Poor water quality: Degradation of water quality due to human impact is also a threat to the health of ecologically important seagrass communities. Nutrient enrichment, caused by inorganic and organic nitrogen and phosphorus loading from urban and agricultural land run-off, can stimulate increased algal growth. This algal growth can smother Johnson's seagrass by shading rooted vegetation and diminishing the water’s oxygen content.

6.Construction and water shading: Construction projects can disturb seagrass habitat. Docks and other structures built over seagrass beds can shade them, decreasing growth and production, or even cause death.

Research is ongoing on ways to successfully grow the species in captivity and transplant it to suitable locations.

Conservation notes 5

Importance to Humans and Estuaries

Johnson’s seagrass plays a major role in the health of benthic resources as a shelter and nursery habitat for other animals. This seagrass has been documented as a food source for endangered West Indian manatees and threatened green sea turtles. Their wider ecological role includes nutrient recycling, detritus production and export, and stabilization of sediments.

How to Help Protect This Species

Johnson’s seagrass grows in estuaries, and is susceptible to water pollution, plus damage to and alteration of riparian zones. Suggested methods to protect this species include:

•Minimize runoff of neighborhood pollutants, fertilizer, and sedimen into local streams are helpful to this species or other stream and estuary dwelling species.

•Join a stream or watershed advocacy group in your area to protect your local estuary ecosystems

•Support restoration of more natural water flow regimes.

•Support conservation programs that work to protect the endangered populations.

•Support research on basic reproductive biology and life history of the species as well as general management and coordination among responsible local, state, and federal agencies.

Sources and Credits

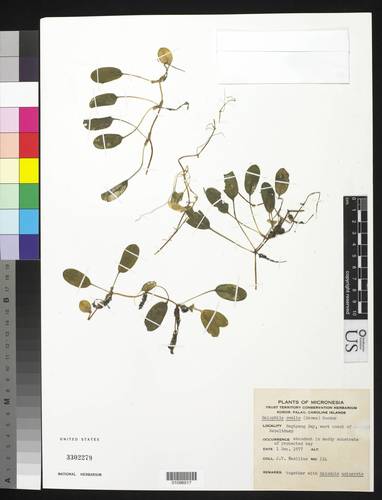

- (c) Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of Natural History, Department of Botany, some rights reserved (CC BY-NC-SA), https://collections.nmnh.si.edu/services/media.php?env=botany&irn=10176528

- (c) Ria Tan, some rights reserved (CC BY-NC-SA), http://farm1.static.flickr.com/165/437144679_0a5e76ed27.jpg

- Hemprich F.G. & Ehrenberbg C.G., no known copyright restrictions (public domain), http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Halophila_ovalis.jpg

- Adapted by GTMResearchReserve from a work by (c) Wikipedia, some rights reserved (CC BY-SA), http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Halophila_ovalis

- (c) GTMResearchReserve, some rights reserved (CC BY-SA)

More Info

- iNat taxon page

- African Plants - a photo guide

- Atlas of Living Australia

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- BOLD Systems BIN search

- eFloras.org

- Flora of North America (beta)

- Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF)

- HOSTS - a Database of the World's Lepidopteran Hostplants

- IPNI (with links to POWO, WFO, and BHL)

- NatureServe Explorer 2.0

- SEINet Symbiota portals

- Tropicos

- USDA PLANTS database

- World Flora Online