Loblolly Pine

Pinus taedaSummary 6

Pinus taeda, commonly known as loblolly pine. is one of several pines native to the Southeastern United States, from central Texas east to Florida, and north to Delaware and Southern New Jersey. The wood industry classifies the species as a southern yellow pine. U.S. Forest Service surveys found that loblolly pine is the second most common species of tree in the United States, after red maple.

Associated forest cover 7

Loblolly pine is found in pure stands and in mixtures with other pines or hardwoods, and in association with a great variety of lesser vegetation. When loblolly pine predominates, it forms the forest cover type Loblolly Pine (Society of American Foresters Type 81) (31). Within their natural ranges, longleaf, shortleaf, and Virginia pine (Pinus palustris, P. echinata, and P. virginiana), southern red, white, post, and blackjack oak (Quercus falcata, Q. alba, Q. stellata, and Q. marilandica), sassafras (Sassafras albidum), and persimmon (Diospyros virginiana) are frequent associates on well-drained sites. Pond pine (Pinus serotina), spruce pine (P. glabra), blackgum (Nyssa sylvatica), red maple (Acer rubrum), and water oak (Quercus nigra), willow oak (Q. phellos), and cherrybark oak (Q. falcata var. pagodifolia) are common associates on moderately to poorly drained sites. In the southern part of its range, loblolly frequently is found with slash pine (Pinus elliottii) and laurel oak (Quercus laurifolia).

In east Texas, southern Arkansas, Louisiana, and the lower Piedmont, loblolly and shortleaf pine are often found in mixed stands. In Loblolly Pine-Shortleaf Pine (Type 80), loblolly predominates except on drier sites and at higher elevations. When shortleaf pine predominates, the mixture forms Shortleaf Pine (Type 75).

In fertile, well-drained coves and along stream bottoms, especially in the eastern part of the range, yellow-poplar (Liriodendron tulipifera), American beech (Fagus grandifolia), and white and Carolina ash (Fraxinus americana and F. caroliniana) are often found in the Loblolly Pine-Shortleaf Pine cover type.

Loblolly pine also grows in mixture with hardwoods throughout its range in Loblolly Pine-Hardwood (Type 82). On moist to wet sites this type often contains such broadleaf evergreens as sweetbay (Magnolia virginiana), southern magnolia (M. grandiflora), and redbay (Persea borbonia), along with swamp tupelo (Nyssa aquatica), red maple, sweetgum, water oak, cherrybark oak, swamp chestnut oak (Quercus michauxii), white ash, American elm (Ulmus americana), and water hickory (Carya aquatica). Occasionally, slash, pond, and spruce pine are present.

In the Piedmont and in the Atlantic Plain of northern Virginia and Maryland, loblolly pine grows with Virginia Pine (Type 79). In northern Mississippi, Alabama, and in Tennessee it is a minor associate in the eastern redcedar-hardwood variant of Eastern Redcedar (Type 46). On moist lower Atlantic Plain sites loblolly pine is found in Longleaf Pine (Type 70), Longleaf Pine-Slash Pine (Type 83), and Slash Pine-Hardwood (Type 85).

In the flood plains and on terraces of major rivers (except the Mississippi River) loblolly pine is a minor associate in Swamp Chestnut Oak-Cherrybark Oak (Type 91). On moist, lower slopes in the Atlantic Plain it is an important component in the Sweetgum-Yellow Poplar (Type 87). In bays, ponds, swamps, and marshes of the Atlantic Plain it is a common associate in Pond Pine (Type 98), the cabbage palmetto-slash pine variant of Cabbage Palmetto (Type 74), and Sweetbay-Swamp Tupelo-Red Bay (Type 104).

There is a great variety of lesser vegetation found in association with loblolly pine. Some common understory trees and shrubs include flowering dogwood (Cornus florida), American holly (Ilex opaca), inkberry (I. glabra), yaupon (I. vomitoria), hawthorn (Crataegus spp.), southern bayberry (Myrica cerifera), pepperbush (Clethra spp.), sumac (Rhus spp.), and a number of ericaceous shrubs. Some common herbaceous species include bluestems (Andropogon spp.), panicums (Panicum spp.), sedges (Carex spp.and Cyperus spp.), and fennels (Eupatorium spp.).

Fire ecology 8

More info for the terms: resistance, tree

Loblolly pine is considered fire resistant [9,56]. Mature loblolly pine

survives low- to moderate-severity fires because of relatively thick bark

and tall crowns. Loblolly pine's fire resistance increases with bark

thickness and tree diameter. Young pines become resistant to

low-severity fire by age 10 [59]. Needles are low in resin and not

highly flammable [36]. Loblolly pine can endure some fire defoliation

[9]. It is not as fire resistant as longleaf pine (Pinus palustris) or

slash pine (P. elliottii) [28]. Abundant regeneration occurs on soil

exposed by fire [7]. Once loblolly pine is big enough to resist fire

damage, frequent summer fire will create and maintain a pine-grassland

community [63].

Flowering and fruiting 9

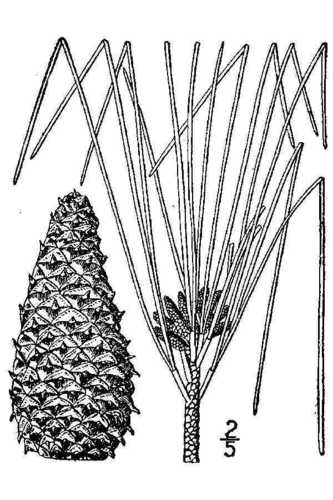

Loblolly pine is monoecious; male flowers form in clusters at the tip of the preceding year's growth and female flowers form on the new year's growth. The pollen-bearing staminate flowers are catkin-like in appearance; they range from 2.5 to 3.8 cm (1.0 to 1.5 in) in length and vary from light green to red and yellow depending on stage of development. The pistillate flowers are generally ovoid and range from 1.0 to 1.5 cm (0.4 to 0.6 in) in length. They vary from light green through shades of pink to red depending on stage of development.

Flowering of loblolly pine is initiated in July and August in a quiescent bud that is set from middle June to early July. The male strobili form in this bud in late July and the female in August, but they are not differentiated into recognizable structures until late September or October. In October the staminate buds develop at the base of a vegetative bud and the pistillate buds develop at the apex of a vegetative bud a few weeks later; both remain dormant until early February (37,41). The date of peak pollen shed depends on the accumulation of 353° C (636° F) day-heat units above 13° C (55° F) after February 1 (16). Flowering is also related to latitude, beginning earlier at lower latitudes than at higher ones, and it can occur between February 15 and April 10. Staminate flowers on a given tree tend to mature before the pistillate flowers, which helps to reduce self-pollination. Fertilization of the pistillate strobili takes place in the spring of the following year (37).

Loblolly pine does not normally flower at an early age, although flowering has been induced on young grafts with scion age of only 3 years. The phenomenon of inducing such early flowering in seedlings is dependent on reducing vegetative shoot growth so that quiescent buds are formed in the latter part of the growing season to allow for the initiation and differentiation of reproductive structures. The formation of quiescent buds in seedlings and saplings does not usually occur during that period because four to five growth flushes are common for trees of this age. As a loblolly pine tree ages, the number of growth flushes decreases, which accounts in part for increased flowering of trees at older ages. Flowering is also genetically controlled and is influenced by moisture (May-July rainfall) and nutrient stresses.

Importance to livestock and wildlife 10

More info for the term: cover

Loblolly pine seeds are an important food source for birds and small

mammals. More than 20 songbirds feed on loblolly pine seeds, and the

seeds make up more than half the diet of the red crossbill. Deer and

rabbit browse seedlings [59]. Loblolly pine stands provide cover and

habitat for white-tailed deer, northern bobwhite, wild turkey, and grey

and fox squirrels. Old-growth loblolly pine provides nesting habitat

for the endangered red-cockaded woodpecker [3].

Reaction to competition 11

Loblolly pine is moderately tolerant when young but becomes intolerant of shade with age. Its shade tolerance is similar to that of shortleaf and Virginia pines, less than that of most hardwoods, and more than that of slash and longleaf pines (31,37,108). Loblolly pine is most accurately classed as intolerant of shade.

Succession in loblolly pine stands that originate in old fields and cutover lands exhibit a rather predictable pattern. The more tolerant hardwoods (including various species of oaks and hickories, sweetgum, blackgum, beech, magnolia, holly, and dogwood) invade the understory of loblolly pine stands and, with time, gradually increase in numbers and in basal area. The hardwoods finally share dominance with each other and with loblolly pine (37,83,100).

The climax forest for the loblolly pine type has been described as oak-hickory, beech-maple, magnolia-beech, and oak-hickory-pine in various parts of its range (28,37). Others view the climax forest as several possible combinations of hardwood species and loblolly pine. There is evidence that within the range of loblolly pine several different tree species could potentially occupy a given area for an indefinite period of time and that disturbance is a naturally occurring phenomenon. If this is so, then the climax for this southern forest might best be termed the southern mixed hardwood-pine forest (83).

Competition affects the growth of loblolly pine in varying degrees depending on the site, the amount and size of competing vegetation, and age of the loblolly pine stand. Across the southern region, average loss of volume production resulting from hardwood competition has been estimated at 25 percent in natural stands and 14 percent in plantations (35). In a North Carolina study, residual hardwoods after logging reduced cubic-volume growth of a new stand of loblolly pine by 50 percent at 20 years, and where additional small hardwoods of sprout and seedling origin were present, growth was reduced by another 20 percent by age 20 (10,64). Similar growth responses in young seedling and sapling stands have been observed in Arkansas, Louisiana, and Texas (24,26,39). Although several short-term studies (5 years or less) of the effects of understory hardwoods on growth of older loblolly pine did not show measurable effects (58), a long-term study (11 to 14 years) showed growth increases of 20 to 43 percent in cubic volume and 21 to 54 percent in board-foot volume after removal of understory vegetation (39). Control of both residual overstory and understory hardwoods is a financially attractive silvicultural treatment for loblolly pine management (10).

Silvicultural practices such as prescribed burns, the use of herbicides, and mechanical treatments arrest natural succession in loblolly pine stands by retarding the growth and development of hardwood understories. Prescribed fire is effective for manipulating understory vegetation, reducing excessive fuel (hazard reduction), disposing of logging slash, preparing planting sites and seedbeds, and improving wildlife habitat. Responses of the understory to prescribed fire varies with frequency and season of burning. Periodic winter burns keep hardwood understories in check, while a series of annual summer burns usually reduces vigor and increases mortality of hardwood rootstocks (62). In the Atlantic Coastal Plain, a series of prescribed bums, such as a winter bum followed by three annual summer bums before a harvest cut, has been more effective than disking for control of competing hardwood vegetation and improvement of pine seedling growth after establishment of natural regeneration (103,104).

Loblolly pine expresses dominance early, and various crown classes develop rapidly under competition on good sites; but in dense stands on poor sites, expression of dominance and crown differentiation are slower (37).

Dense natural stands of loblolly pine usually respond well to precommercial thinning. To ensure, the best volume gains, stocking should be reduced to 1,235 to 1,730 stems per hectare (500 to 700/acre) by age 5. When managing for sawtimber, thinnings increase diameter growth of residual trees and allow growth to be put on the better trees in the stand, thus maximizing saw-log volume growth and profitability (56,78).

Loblolly pines that have developed in a suppressed condition respond in varying degrees to release. Increases in diameter growth after release are related to live-crown ratio and crown growing space, but trees of large diameter generally respond less than trees of small diameter. Trees with well-developed crowns usually respond best to release. Trees long suppressed may also grow much faster in both height and diameter after release but may never attain the growth rate of trees that were never suppressed (37,75).

Loblolly pine can be regenerated and managed with any of the four recognized reproduction cutting methods and silvicultural systems. Even-aged management is most commonly used on large acreages; however, uneven-aged management with selection cutting has proved to be a successful alternative.

Special uses 12

Natural loblolly pine stands as well as intensively managed plantations provide habitat for a variety of game and nongame wildlife species. The primary game species that inhabit pine and pine-hardwood forests include white-tailed deer, gray and fox squirrel, bobwhite quail, wild turkey, mourning doves, and rabbits (94). Some of these species utilize the habitat through all stages of stand development, while others are attracted for only a short time during a particular stage of development. For example, a loblolly pine plantation can provide forage for deer only from the time of planting to crown closure. Without modifying management practices, this usually occurs in 8 to 10 years (13). Bobwhite tend to use the plantation until a decline in favored food species occurs (20). As the habitat deteriorates, deer and quail usually move to mature pine or pine-hardwood forests (47) or to other newly established plantations. Management modifications such as wider planting spacing and early and frequent thinnings will delay crown closure, and periodic prescribed bums will stimulate wildlife food production.

Wild turkeys inhabit upland pine and pine-hardwood forests and do particularly well on large tracts of mature timber with frequent openings and where prescribed burning is conducted (96,97).

Pine lands are the chief habitat for some birds such as the pine warbler, brown-headed nuthatch, and Bachman's warbler. Old-growth stands are very important to the existence of the red-cockaded woodpecker. Large loblolly pine trees are favorite roosting places for many birds and provide an important nesting site for ospreys and the bald eagle (46).

In urban forestry, loblolly pines often are used as shade trees and for wind and noise barriers throughout the South. They also have been used extensively for soil stabilization and control of areas subject to severe surface erosion and gullying. Loblolly pine provides rapid growth and site occupancy and good litter production for these purposes (114,115).

Biomass for energy is currently being obtained from precommercial thinnings and from logging residue in loblolly pine stands. Utilization of these energy sources will undoubtedly increase, and loblolly pine energy plantations may become a reality.

Sources and Credits

- (c) Lance and Erin, some rights reserved (CC BY-NC-ND), https://www.flickr.com/photos/lance_mountain/446647634/

- (c) Alicia Pimental, some rights reserved (CC BY), http://www.flickr.com/photos/16055430@N03/4550963269

- (c) Biodiversity Heritage Library, some rights reserved (CC BY), https://www.flickr.com/photos/biodivlibrary/7797061464/

- (c) Marcus Q on Flickr, some rights reserved (CC BY-SA), https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/8/8a/Pinus_taeda_cones.jpg

- (c) "<a href=""http://www.knps.org"">Kentucky Native Plant Society</a>. Scanned by <a href=""http://www.omnitekinc.com/"">Omnitek Inc</a>.", some rights reserved (CC BY-NC-SA), http://plants.usda.gov/java/largeImage?imageID=pita_001_avd.tif

- Adapted by Jonathan (JC) Carpenter from a work by (c) Wikipedia, some rights reserved (CC BY-SA), http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pinus_taeda

- (c) Unknown, some rights reserved (CC BY-NC), http://eol.org/data_objects/22777690

- Public Domain, http://eol.org/data_objects/24642583

- (c) Unknown, some rights reserved (CC BY-NC), http://eol.org/data_objects/22777691

- Public Domain, http://eol.org/data_objects/24642575

- (c) Unknown, some rights reserved (CC BY-NC), http://eol.org/data_objects/22777697

- (c) Unknown, some rights reserved (CC BY-NC), http://eol.org/data_objects/22777699

More Info

- iNat taxon page

- Atlas of Living Australia

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- BOLD Systems BIN search

- eFloras.org

- Flora of North America (beta)

- Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF)

- HOSTS - a Database of the World's Lepidopteran Hostplants

- IPNI (with links to POWO, WFO, and BHL)

- Maryland Biodiversity Project

- NatureServe Explorer 2.0

- New Zealand Plant Conservation Network

- SEINet Symbiota portals

- Tropicos

- USDA PLANTS database

- World Flora Online

- 日本のレッドデータ検索システム

- 植物和名−学名インデックス YList