Pacific Madrone

Arbutus menziesiiSummary 7

Arbutus menziesii (Pacific madrona, madrone or Arbutus) is a species of tree in the family Ericaceae, native to the western coastal areas of North America, from British Columbia to California.

Arbutus menziesii 8

Contents

Common names[edit]

It is also known as the madroño, madroña, or bearberry. The name "strawberry tree" (A. unedo) may also be found in relation to A. menziesii. In the United States, the name "madrone" is used south of the Siskiyou Mountains of southern Oregon and Northern California and the name "madrona" is used north of the Siskiyou Mountains, according to the "Sunset Western Garden Book". The Concow tribe calls the tree dis-tā’-tsi (Konkow language) or kou-wät′-chu.[2] In British Columbia it is simply referred to as arbutus. Its species name was given it in honour of the Scottish naturalist Archibald Menzies, who noted it during George Vancouver's voyage of exploration.[3][4]

Description[edit]

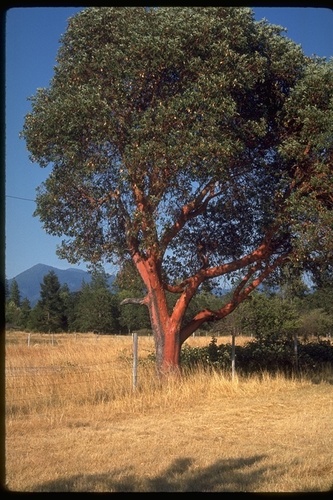

Arbutus menziesii is an evergreen tree with rich orange-red bark that when mature naturally peels away in thin sheets, leaving a greenish, silvery appearance that has a satin sheen and smoothness.[5] The exposed wood sometimes feels cool to the touch. In spring, it bears sprays of small bell-like flowers, and in autumn, red berries.[6] The berries dry up and have hooked barbs that latch onto larger animals for migration. It is common to see madronas of about 10 to 25 metres (33 to 82 ft) in height, but with the right conditions trees may reach up to 30 metres (98 ft). In ideal conditions madronas can also reach a thickness of 5 to 8 feet (1.5 to 2.4 m) at the trunk, much like an oak tree.[citation needed] Leaves are thick with a waxy texture, oval, 7 to 15 centimetres (2.8 to 5.9 in) long and 4 to 8 centimetres (1.6 to 3.1 in) broad, arranged spirally; they are glossy dark green above and a lighter, more grayish green beneath, with an entire margin. The leaves are evergreen, lasting a few years before detaching, but in the north of its range, wet winters often promote a brown to black leaf discoloration due to fungal infections.[7][8] The stain lasts until the leaves naturally detach at the end of their lifespan.Distribution and habitat[edit]

Madronas are native to the western coast of North America, from British Columbia (chiefly Vancouver Island and the Gulf Islands) to California. They are mainly found in Puget Sound, the Oregon Coast Range, and California Coast Ranges; but are also scattered on the west slope of the Sierra Nevada and Cascade mountain ranges. They are rare south of Santa Barbara County, with isolated stands south to Palomar Mountain in California.[5] One author lists their southern range as extending as far as Baja California in Mexico,[9] but others point out that there are no recorded specimens collected that far south,[5] and the trees are absent from modern surveys of native trees there.[10]

Cultivation[edit]

The trees are difficult to transplant and a seedling should be set in its permanent spot while still small.[8] Transplant mortality becomes significant once a madrona is more than 1 foot (30 cm) tall. The site should be sunny (south- or west-facing slopes are best), well drained, and lime-free (although occasionally a seedling will establish itself on a shell midden). In its native range, a tree needs no extra water or food once it has become established. Water and nitrogenfertilizer will boost its growth, but at the cost of making it more susceptible to disease.[citation needed]

This plant has gained the Royal Horticultural Society's Award of Garden Merit.[11]

Uses[edit]

Native Americans ate the berries, but because the berries have a high tannin content and are thus astringent, they more often chewed them or made them into a cider. They also used the berries to make necklaces and other decorations, and as bait for fishing. Bark and leaves were used to treat stomachaches, cramps, skin ailments, and sore throats. The bark was often made into a tea to be drunk for these medicinal purposes.[12][13] Many mammal and bird species feed off the berries,[14] including American robins, cedar waxwings, band-tailed pigeons, varied thrushes, quail, mule deer, raccoons, ring-tailed cats, and bears. Mule deer will also eat the young shoots when the trees are regenerating after fire.[5][12] It is also important as a nest site for many birds,[12] and in mixed woodland it seems to be chosen for nestbuilding disproportionately to its numbers.[citation needed] The wood is durable and has a warm color after finishing, so it has become more popular as a flooring material, especially in the Pacific Northwest.[15] An attractive veneer can also be made from the wood.[16] However, because large pieces of madrona lumber warp severely and unpredictably during the drying process, they are not used much.[4] Madrone is burned for firewood, though,[12][17] since it is a very hard and dense wood that burns long and hot, surpassing even oak in this regard.Conservation[edit]

Although drought tolerant and relatively fast growing, Arbutus menziesii is currently declining throughout most of its range. One likely cause is fire control; under natural conditions, the madrona depends on intermittent naturally occurring fires to reduce the conifer overstory.[3][5][12] Mature trees survive fire, and can regenerate more rapidly after fire than the Douglas firs with which they are often associated. They also produce very large numbers of seeds, which sprout following fire.[5]

Increasing development pressures in its native habitat have also contributed to a decline in the number of mature specimens. This tree is extremely sensitive to alteration of the grade or drainage near the root crown. Until about 1970, this phenomenon was not widely recognized on the west coast; thereafter, many local governments have addressed this issue by stringent restrictions on grading and drainage alterations when Arbutus menziesii trees are present.[citation needed] The species is also affected to a small extent by sudden oak death, a disease caused by the water-mold Phytophthora ramorum.[5]

References[edit]

- ^ This species was originally described and published in Flora Americae Septentrionalis; or, a Systematic Arrangement and Description of the Plants of North America 1:282. 1813–1814. GRIN (April 25, 2003). "Arbutus menziesii information from NPGS/GRIN". Taxonomy for Plants. National Germplasm Resources Laboratory, Beltsville, Maryland: USDA, ARS, National Genetic Resources Program. Retrieved August 5, 2010.

- ^Chesnut, p. 406

- ^ abMcDonald, Philip M.; Tappeiner, II, John C. "Pacific Madrone". U.S. Forest Service. Retrieved May 24, 2013.

- ^ abLang, Frank A. "Pacific madrone". The Oregon Encyclopedia. Portland State University. Retrieved May 24, 2013.

- ^ abcdefgReeves, Sonja L. "Arbutus menziesii". Fire Effects Information System. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory. Retrieved September 22, 2012.

- ^"Pacific Madrone". Washington State Department of Ecology. Retrieved May 24, 2013.

- ^Metcalf, pp. 69–70

- ^ abRichards, Davi (April 20, 2006). "The majestic, demanding madrone". The Register-Guard (Eugene, Oregon). p. 26 (Home & Garden). Retrieved May 24, 2013.

- ^Hitchcock, Charles Leo (1959). Vascular Plants of the Pacific Northwest: Part 4 Ericaceae through Campanulaceae. University of Washington Press.

- ^Minnich, Richard A; Franco-Vizcaino, Ernesto (1997). "Mediterranean vegetation of northern Baja California". Fremontia25 (3).

- ^"RHS Plant Selector Arbutus menziesii AGM / RHS Gardening". Apps.rhs.org.uk. Retrieved August 29, 2012.

- ^ abcde"Pacific Madrone" (PDF). USDA Plant Guide. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service. April 5, 2002. Retrieved May 25, 2013.

- ^Seagrave, John (December 11, 2002). "The Biogeography of the Pacific Madrone (Arbutus menziesii)". San Francisco State University. Retrieved May 25, 2013.

- ^Niemiec, et al., p. 82

- ^"Pacific Madrone Flooring". Sustainable Northwest Wood. Retrieved May 25, 2013.

- ^"Madrone Wood Veneer Information". Wood River Veneer. Retrieved May 25, 2013.

- ^Niemiec, et al., pp. 81, 86

Works cited[edit]

- Chesnut, Victor King (January 24, 1902). Plants used by the Indians of Mendocino County, California. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. Retrieved August 24, 2012.

- Metcalf, Woodbridge (1959). Native Trees of the San Francisco Bay Region. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. ISBN 0520008537. OCLC 2631060.

- Niemiec, Stanley S.; Ahrens, Glenn R.; Hibbs, David E. (March 1995). "Hardwoods of the Pacific Northwest" (PDF). Oregon State University. Retrieved May 25, 2013.

Sources and Credits

- (c) M.E. Sanseverino, some rights reserved (CC BY-NC-ND), http://www.flickr.com/photos/14563577@N00/3383844774

- (c) 2012 Al Keuter, some rights reserved (CC BY-NC-SA), http://calphotos.berkeley.edu/cgi/img_query?seq_num=408987&one=T

- (c) 1999 California Academy of Sciences, some rights reserved (CC BY-NC-SA), http://calphotos.berkeley.edu/cgi/img_query?seq_num=24308&one=T

- (c) 2006 California Academy of Sciences, some rights reserved (CC BY-NC-SA), http://calphotos.berkeley.edu/cgi/img_query?seq_num=204486&one=T

- (c) 2008 Keir Morse, some rights reserved (CC BY-NC-SA), http://calphotos.berkeley.edu/cgi/img_query?seq_num=267397&one=T

- (c) 2008 Keir Morse, some rights reserved (CC BY-NC-SA), http://calphotos.berkeley.edu/cgi/img_query?seq_num=267398&one=T

- (c) Wikipedia, some rights reserved (CC BY-SA), http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arbutus_menziesii

- (c) Unknown, some rights reserved (CC BY-SA), http://eol.org/data_objects/32430210

More Info

- iNat taxon page

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- BOLD Systems BIN search

- Calflora

- CalPhotos

- eFloras.org

- Flora of North America (beta)

- Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF)

- HOSTS - a Database of the World's Lepidopteran Hostplants

- IPNI (with links to POWO, WFO, and BHL)

- Jepson eFlora

- NatureServe Explorer 2.0

- New Zealand Plant Conservation Network

- OregonFlora.org

- SEINet Symbiota portals

- Tropicos

- USDA PLANTS database

- VASCAN by Canadensys

- World Flora Online