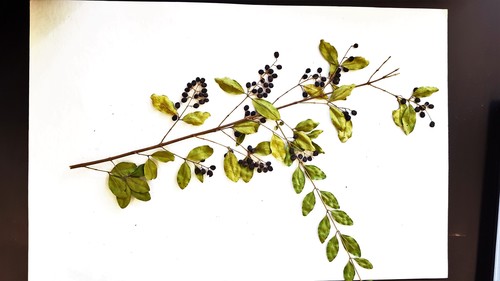

Chinese privet

Ligustrum sinenseDescription 12

More info for the terms: shrub, shrubs

Privets are nonnative shrubs or trees with smooth bark and slender twigs [1,21,65]. Leaves are opposite, and fruits are drupes produced in panicles [9,20,25,43,67,75]. Amur privet is a 12- to 16-foot-tall (3.7-5 m) shrub [1,62]. Japanese privet and Chinese privet are tall shrubs or small trees, 10 to 39 feet (3-12 m) tall, with trunks often clumped and inclined [20,43,67]. European privet is a 10- to 16-foot-tall (3-5 m), much-branched shrub [19,54,71].

Amur privet is considered deciduous [62]. Japanese privet is considered evergreen [20,62,75]. Leaf retention in Chinese privet and European privet is variable and is presumably dependent upon multiple site factors such as drought, shading, and temperature. These species have been described as deciduous [54,71,75], tardily deciduous [20], semideciduous [65], somewhat evergreen [65], half-evergreen [3,19,54,71], and evergreen [25,65]. Urbatsch [65] indicates European privet is relatively more deciduous than Chinese privet.

Japanese privet is single seeded. Seeds are somewhat rounded and wrinkled on 1 side; the other surfaces plane. Chinese privet fruits yield 1-2 seeds each [67]. Leaf and fruit size data are listed below. leaf size fruit size length width diameter length Amur privet ≥2 inches (5 cm) [43] ≤1 inch (2.5 cm) [43] 0.24-0.32 inch (6-8 mm) [43]

Japanese privet 1.2-3.9 inches (3-10 cm) [9,20,43,67,75] 1-2 inches (2.5-5 cm) [20,43] ~0.2 inch (5 mm) [20,43,67] 0.24-0.47 inch (6-12 mm) [20,43,67] Chinese privet 0.6-2.8 inch (1.5-7 cm) [9,20,25,43,67] 0.5-1 inch (1.3-2.5 cm) [20,43,67] 0.16-0.24 inch (4-6 mm) [20,43,67] 0.16-0.28 inch (4-7 mm) [20,43,67] European privet 0.8-2.4 inches (2-6 cm) [19,25,54,71] 0.3-0.8 inch (0.8-2 cm) [71] 0.16-0.24 inch (4-6 mm) [54]

In general, autecological information about privets is lacking. In particular, such information about Japanese privet is sparse, and information about Amur privet is absent from the literature.

The preceding description provides characteristics of privet that may be relevant to fire ecology and is not meant to be used for identification. Keys for identifying privets are available (e.g. [9,11,19,20,27,37,43,69,75]). See Plants Database and the Louisiana State University Agcenter's websites for photos and descriptive characteristics.

Description and biology 13

- Plant: deciduous or semi-evergreen shrubs that grow from 8-20 ft. tall; trunks with multiple stems with long leafy branches; the presence or absence of hairs and type of hairs on stems is helpful in distinguishing species.

- Leaves: opposite, simple, entire, short-stalked, ranging in length from 1-3 in. and varying in shape from oval, elliptic to oblong.

- Flowers, fruits and seeds: flowers small, white and tubular with four petals and occur in clusters at branch tips; fragrant; late spring to early summer (May to July); length of corolla tube length ranges from 1/10 in. (Chinese) to ¼ in. (border); anthers exceed the corolla lobes (Chinese and California); fruit is small black to blue-black oval to spherical drupe (i.e., a fleshy fruit with 1-several stony seeds inside), mature late summer to fall.

- Spreads: by birds that consume fruits and excrete seeds undamaged in new locations; can spread locally through root sprouting.

Impacts and control 14

More info for the terms: fire management, hardwood, mesic, natural, presence, relict, restoration, shrub

Impacts: In many areas of North America, privet easily escapes cultivation and can quickly degrade native communities by forming dense monospecific stands [1]. In a survey of federal wilderness managers, privet was mentioned among "widely reported problem species" in Alabama, Arkansas, and Kentucky [32].

Japanese privet escapes into natural areas in southern North America where it can form "dense, impenetrable thickets" and displace native species [31]. One example is in natural areas around Austin, Texas, where Japanese privet has invaded intermittent stream bed and mesic woodland habitats. Its impacts include outcompeting native woody species such as wax mallow (Malvaviscus arborea var. drummondii), Mexican buckeye (Ungnadia speciosa), American beautyberry (Callicarpa americana), small palmleaf thoroughwort (Conoclinium greggii), pecan (Carya illinoensis), and Texas ash (Fraxinus texensis). Removal of Japanese privet from these areas has resulted in regrowth of other native species, including mescalbean sophora (Sophora secundiflora), Buckley oak (Quercus buckleyi), live oak (Quercus virginiana), southwestern bristlegrass (Setaria scheelei), toothleaf goldeneye (Viguiera dentata), white crownbeard (Verbesina virginica), Rio Grande palmetto (Sabal mexicana), rougeplant (Rivina humilis), and Drummond's woodsorrel (Oxalis drummondii) [53].

Chinese privet invades natural areas throughout much of southern and eastern North America. It has been reported as a problem weed on Nature Conservancy preserves in Alabama, Arkansas, Louisiana, Georgia, Florida, Mississippi, Tennessee, and North Carolina [1]. Chinese privet establishes monospecific stands that dominate the forest shrub layer and shade out herbaceous plants, altering species composition and community structure [11,31,68]. Increasing abundance of Chinese privet in the understory of eastern bottomland forests may hinder regeneration of native hardwood species [4].

An example of the impacts of Chinese privet on native plant diversity is in southern Florida, where it has invaded undisturbed relict slope hammock habitat, threatening to displace the rare Miccosukee gooseberry (Ribes echinellum) [64]. Miccosukee gooseberry is federally listed as threatened [63] and state listed as endangered in Florida [15].

Impacts of European privet on native North American flora are mixed. It has been reported as a problem weed on Nature Conservancy preserves in Arkansas, Tennessee, and Ohio [1], but there are fewer reports of negative impacts from invasive European privet in North America than for Chinese privet. Gayek and Quigley [18] describe valley bottoms in a southwestern Ohio mixed mesophytic forest where European privet has been growing for at least 40 years. Their studies indicate that European privet generally does not compete well in the understories of these forests. Even in moist valley bottoms where it establishes mature stems, European privet coexists with a variety of native perennials and spring "wildflowers" [18]. More research is needed to determine where escaped European privet poses the greatest threat to North American natural areas.

Control: Perhaps the most important aspect of controlling privet is managing sprouting that often occurs subsequent to initial control treatments (see Asexual regeneration). Control methods that remove or damage aboveground stems, such as mechanical cutting or prescribed burning, will likely cause sprouting. Subsequent monitoring and repeated treatments may be necessary to eliminate sprouting stems.

Prevention: Preventing the influx of privet seed from relatively distant sources may be impossible due to dispersal by birds. Preventing establishment of dense, seed-producing populations in managed natural areas will increase the probability of successful restoration programs [1]. Frequent monitoring may be necessary in areas near a privet seed source or in areas that were recently treated to control existing privet infestations. Young Chinese privet seedlings (stem diameter < 1 inch (25 mm) and height < 8 inches (20 cm)) are able to produce "substantial" amounts of fruit [72]. Young privet stems of sprout origin might also be capable of contributing seed soon after control treatments.

Integrated management: No information

Physical/mechanical: Seedlings can be removed by hand-pulling. When hand-pulling seedlings, the entire root system must be extracted to prevent sprouting. Established seedlings become increasingly difficult to hand-pull because of a strong root system [68].

Mowing and/or cutting can reduce the spread of privet by preventing seed production. Repeated cutting may eventually eradicate privet [1]. Stems larger than 1 inch (2.5 cm) in diameter may be most easily controlled by cutting close to ground level and applying herbicides to the cut stumps [30,53,68]. Cutting stems without accompanying herbicide treatment will likely promote growth from sprouting. Even with repeated follow-up cutting, mechanical control alone may be difficult [68].

Fire: See Fire Management Considerations.

Biological: No information

Grazing/browsing: Domestic goats can provide some control, provided privet has not grown beyond browseline [1].

Chemical: Invasive privet can often be effectively controlled by painting cut stumps with herbicides. Areas where this method may be particularly desirable include sparse infestations of large stems, places where stems are concentrated, such as fence lines, or habitats where the presence of desirable native species precludes foliar application [26].

Foliar spraying can also be effective, particularly for dense populations. Late fall or early spring are the best times for foliar spraying, since privet is likely to be biologically active but native species are dormant. Applying herbicide and oil solution to basal stem bark may also kill privet [1].

Below is a list of herbicides that have been tested and judged effective for controlling privets in North America, as well as some special considerations for specific control techniques. There is no information available, as of this writing (2003), concerning chemical control of Amur privet. Japanese privet Chinese privet European privet Chemical(s) Special Considerations Chemical(s) Special Considerations Chemical(s) Special Considerations imazapyr effective for painting cut stumps [53] imazapyr [1,35] effective for painting cut stumps [1] 2,4-D/picloram effective for painting cut stumps [26] glyphosate most effective when applied at bud break or soon thereafter [1] glyphosate [35,68] apply to foliage in late fall after native plant foliage has abscised [1,68] glyphosate effective for painting cut stumps [1] triclopyr [1] triclopyr/picloram effective for painting cut stumps [26] metsulfuron [26,35] metsulfuron [26] glyphosate/X-45 [26,31] effective for painting cut stumps or for foliar application [31]

For more information regarding appropriate use of herbicides against invasive plant species in natural areas, see The Nature Conservancy's Weed control methods handbook. For more information specific to herbicide use against privet, see The Nature Conservancy's Element Stewardship Abstract web page for Ligustrum spp. Cultural: No information

Taxonomy 15

The currently accepted genus name for privet is Ligustrum L. (Oleaceae) [3,19,27,37,43,54,60,62,71,74,75]. This report summarizes information on 4 species

of privet:

Ligustrum amurense Carr. [27] Amur privet

Ligustrum japonicum Thunb. [9,11,20,27,43,60,67,75] Japanese privet

Ligustrum sinense Lour. [9,11,20,27,43,59,74,75] Chinese privet

Ligustrum vulgare L. [3,19,25,27,37,54,60,69,71] European privet

When discussing characteristics common to all 4 species, this report refers to them collectively

as privet or privets. When referring to individual

species, the common names listed above are used.

Sources and Credits

- (c) Kai Yan, Joseph Wong, some rights reserved (CC BY-NC-SA), http://www.flickr.com/photos/33623636@N08/5552058075/

- (c) 2005 Luigi Rignanese, some rights reserved (CC BY-NC), http://calphotos.berkeley.edu/cgi/img_query?seq_num=165522&one=T

- (c) Sam Kieschnick, some rights reserved (CC BY), uploaded by Sam Kieschnick

- (c) Pete The Poet, some rights reserved (CC BY-NC), https://www.flickr.com/photos/17674930@N07/33071689230/

- (c) Leonora (Ellie) Enking, some rights reserved (CC BY-SA), https://www.flickr.com/photos/33037982@N04/7346808454/

- (c) maddie_b, some rights reserved (CC BY-NC), uploaded by maddie_b

- (c) Savannah, some rights reserved (CC BY-NC), uploaded by Savannah

- (c) Laura Clark, some rights reserved (CC BY), uploaded by Laura Clark

- (c) Julie Pearce, some rights reserved (CC BY-NC), uploaded by Julie Pearce

- (c) 2005 Luigi Rignanese, some rights reserved (CC BY-NC), http://calphotos.berkeley.edu/cgi/img_query?seq_num=165529&one=T

- (c) cmcallister, some rights reserved (CC BY-NC)

- Public Domain, http://eol.org/data_objects/24636913

- (c) Unknown, some rights reserved (CC BY-NC-SA), http://eol.org/data_objects/22878018

- Public Domain, http://eol.org/data_objects/24636925

- Public Domain, http://eol.org/data_objects/24264662

More Info

- iNat taxon page

- African Plants - a photo guide

- Atlas of Living Australia

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- BOLD Systems BIN search

- Calflora

- CalPhotos

- Catalogo de Plantas y Líquenes de Colombia

- eFloras.org

- Flora Digital de Portugal

- Flora of North America (beta)

- Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF)

- Go Botany

- HOSTS - a Database of the World's Lepidopteran Hostplants

- IPNI (with links to POWO, WFO, and BHL)

- Jepson eFlora

- Maryland Biodiversity Project

- NatureServe Explorer 2.0

- NBN Atlas

- New Zealand Plant Conservation Network

- OregonFlora.org

- SEINet Symbiota portals

- Tropicos

- USDA PLANTS database

- World Flora Online

- 日本のレッドデータ検索システム

- 植物和名−学名インデックス YList

Range Map

iNat Map

| Flower color | white |

|---|