Observation of the Week, 2/3/16

This Southern Desert Horned Lizard seen by flygrl67 in Joshua Tree National Park, California, is our Observation of the Week!

Michelle C. Torres-Grant (@flygrl67) recalls that “one of my favorite things to do [as a child] was turn over rocks and check out all the critters. All the hidden life amazed and fascinated me.” Her busy life led her away from exploring nature, but when the 2008 recession hit and she had to quit her hobby as an aviator, Michelle says “suddenly I had a lot of time on my hands, and after having lived in San Luis Obispo (SLO) since 1988 I finally decided to start hiking regularly and exploring the local trails.” She has been photographing and documenting her hikes since then.

Michelle has also been a professional architectural photographer since 2012, but lately “photography became almost all work and no play.” Luckily for her (and iNat), she was acquainted with iNaturalist users R.J. Adams (@rjadams55), Christian Schwarz (@leptonia), Damon Tighe (@damontighe), and John Brew (@brewbrooks), who inspired her to make her first iNaturalist post - California’s new State Lichen, seen on a private tour with Christian (see below - from L to R Christian, Professor Tom Volk, Michelle, and Michelle’s husband Leonard). Since then Michelle has posted over ninety observations, many taken from the “hundreds, maybe thousands” of images in her photo vault from all those years of documenting hikes - including this Southern Desert Horned Lizard.

As a flight attendant whose regular route included flights to Palm Springs, Michelle loved seeing the desert in bloom during springtime and in 2010 finally organized a trip there for her 43rd birthday. It was on her birthday when she photographed the Horned Lizard while hiking the Lost Palm Oasis trail in Joshua Tree National Park. “I remember seeing it hanging out right beside the trail, and I found it especially interesting because of its coral coloring, which I had never seen before on a horned lizard, not that I had seen many horned lizards in my life.”

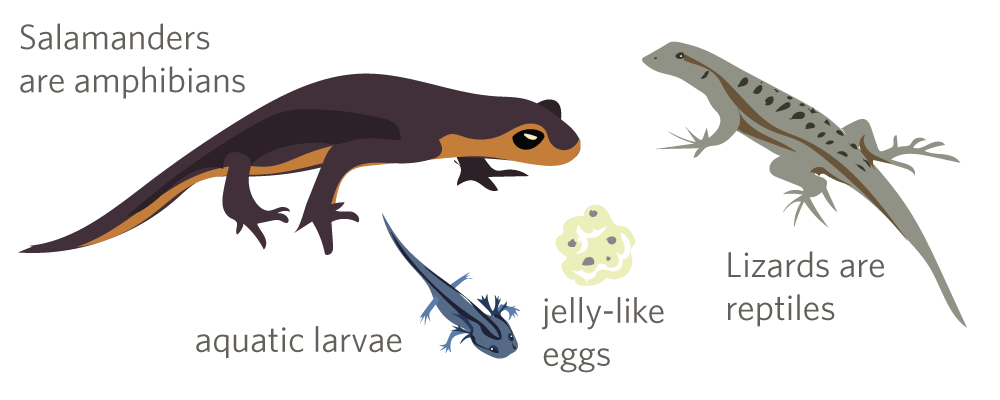

One of the Mojave Desert’s more well-camouflaged reptiles (which Michelle captured wonderfully), Desert Horned Lizards are insectivores who specialize in eating ants. And while some species of Horned Lizard are known for their ability to squirt blood from their eyes as a defensive measure, Desert Horned Lizards cannot. They instead rely on camouflage and frantic scurrying to escape predation.

“I'm enjoying going back through all the old pix, which are bringing up so many memories of some great outings, and it has reminded me to keep exploring the environment,” says Michelle. “My hopes in using iNaturalist are that I'll learn more about my immediate environment and eco-system, and how it fits into the larger ecosystem of our region, the world, and universe.”

- by Tony Iwane

You can check out Michelle’s photos on Flickr here.

Here’s some information about Christian Schwarz’s Redwood Coast Tours.