Observation of the Week, 4/1/16

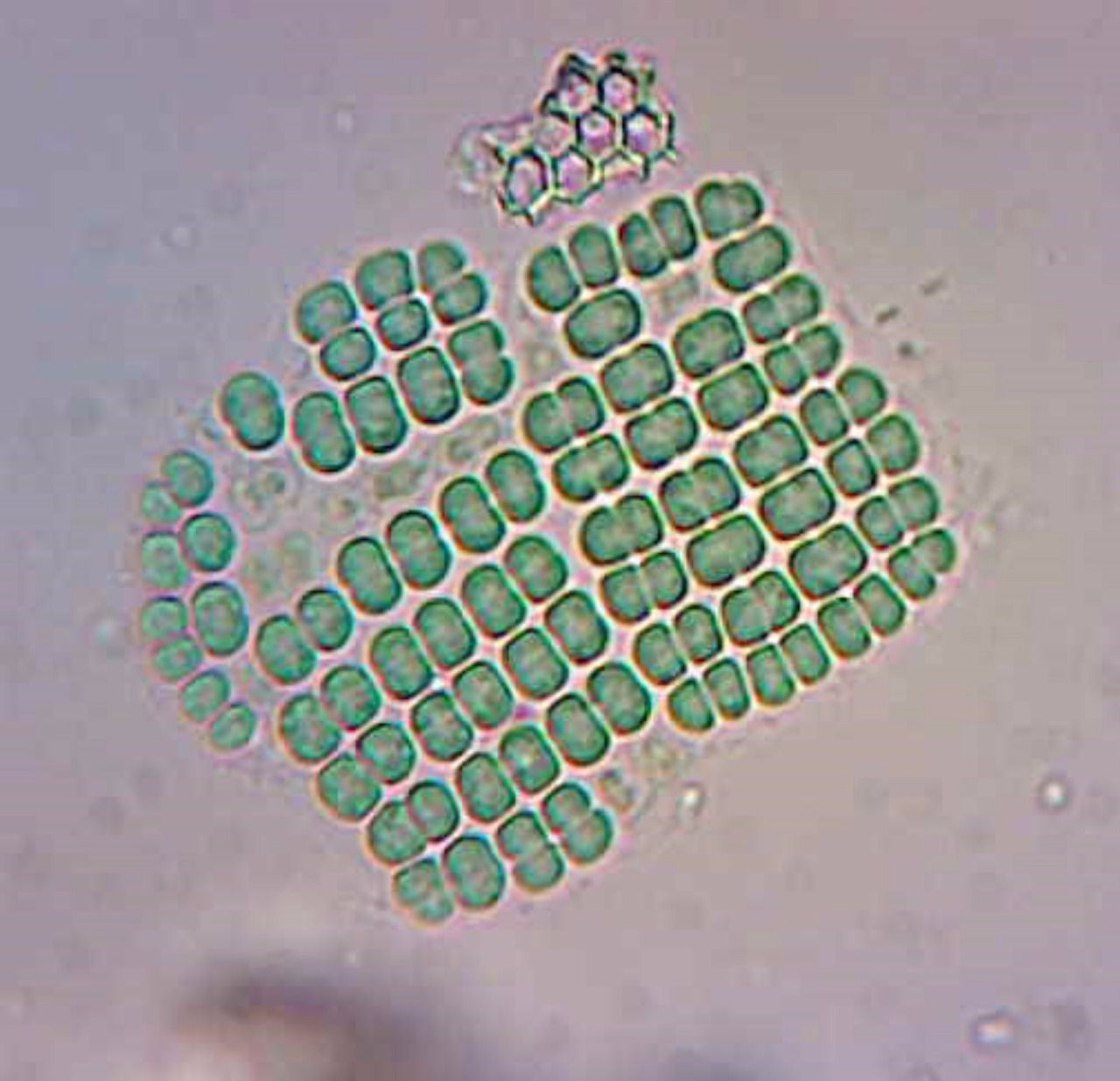

This Merismopedia colony seen by sarka in Florida is our Observation of the Week!

Most observations posted to iNaturalist are of macroscopic life - organisms one can see with the naked eye. Much of life on Earth, however, is microscopic, and we’re lucky enough to have some users who specialize in photographing these exquisite tiny organisms, folks like Sarka Martinez.

When she was a professional with a degree in computer science, Sarka always felt that computer science “was a world that was not really me. I needed to be outside delving into the natural world, a world of discovery and research.” After “retiring,” she now has the opportunity to do things that really interest her - like documenting seaweed, diatoms and other types of plankton in both Washington State and Florida! “I must say that looking at all life in the water is my very best hobby,” she says. “Looking at pollen is pretty awesome too.”

Sarka had her first opportunity to work with “fancy” microscopes while volunteering at the Whitney Marine Laboratory in Florida, documenting seaweeds and looking at their cell structures to get her identifications down to species level. She now documents plankton for SoundToxins.org in Washington for six months of the year, and for NOAA in Florida for the rest of the year.

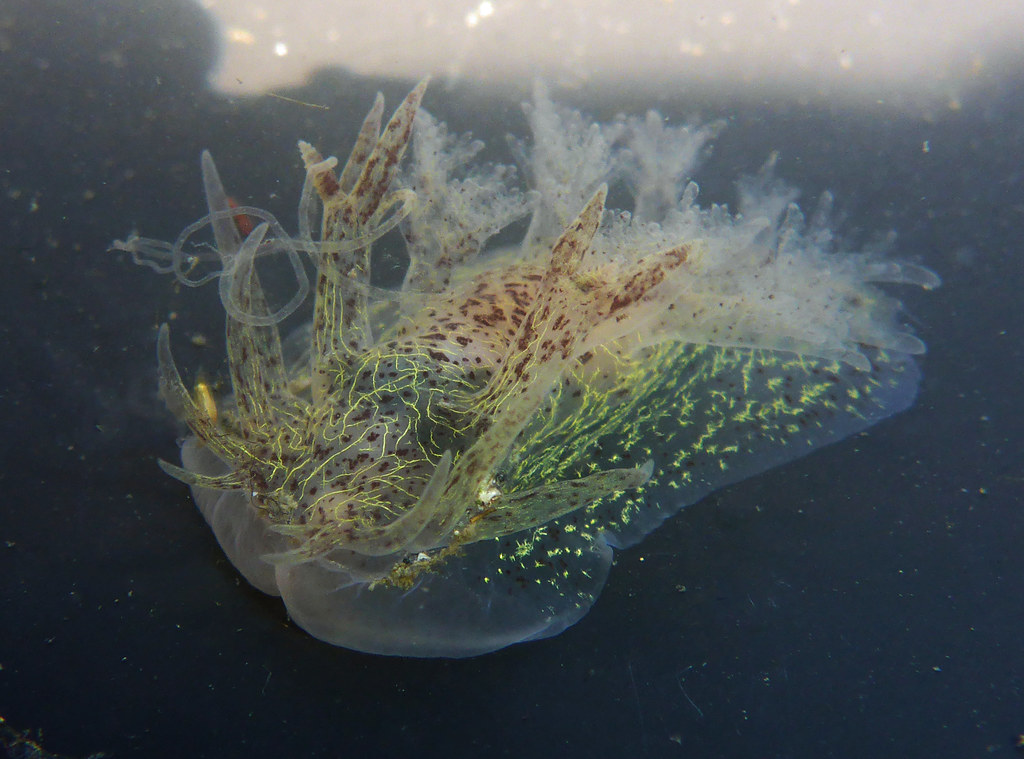

The Merismopedia colony she found in Florida is a type of cyanobacteria, also known as blue-green algae. Ancient organisms, tiny but mighty cyanobacteria are photosynthetic and are believed to have been the cause of the The Great Oxygenation Event 2.3 billion years ago, creating oxygen that accumulated in the atmosphere. Merismopedia is a genus of cyanobacteria, and they divide in only two directions, forming a characteristic grid pattern. Merismopedia can move using filaments called hormogonia.

So how to photograph such a tiny thing? Sarka uses a simple set-up consisting of a used Leitz Laborlux S microscope (bought on eBay) and a cheap Celestron camera that connects to her computer via USB. “Out of 100 images,” she says, “I keep about 20 that turns out to be around 5 organisms.”

“Part of taking photos is to have people tell me if I am identifying them correctly. iNaturalist is a great vehicle to do that and is a great place to store my photos,” says Sarka. She and her husband also use iNaturalist as a motivator to explore new places. “We treat our trips like scavenger hunts, hoping to get an amazing find or to be the first to ‘find’ in the region.”

- by Tony Iwane

- Sarka has two plankton projects on iNaturalist: one for the southeastern US, and one for the Pacific Northwest.

- There is, of course, a Merismopedia video on Youtube. The colony begins to flip around at about 3:17, which is pretty neat to watch.