For over five decades, the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia—Ejército del Pueblo (FARC) guerilla group waged a civil war in Colombia. After FARC signed a ceasefire in 2016, there was an opportunity to explore and survey the biodiverse regions the group had occupied, and the need to incorporate thousands of guerrillas into Colombian society.

The initiative GROW Colombia, supported by the Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF-UK), is working to sustainably develop “Colombia’s agri-industry and bio-economy for the benefit of the Colombian people,” and they are collaborating with Jaime Gonogora (@jaimegongora), an Associate Professor at the University of Sydney and native Colombian. Professor Góngora has been working with the former guerrillas to conduct biodiversity surveys of the areas they occupied, and is using iNaturalist as one of the tools in their work.

I recently spoke with Professor Góngora (above) via Zoom about his work with the former guerrillas and how they are using iNaturalist.

Jaime Góngora grew up in the mountains of Colombia and, after moving to Bogotá, had to work to pay for his university education, becoming the first in his family to graduate from college. “I wasn’t the most talented student at all,” he says, “[but] I knew that I loved biology. I wanted to become an academic, a scientist, [and] conserve nature.” He credits meeting Chris Moran and Frank Nicholas of the University of Sydney, who were doing genetics work, and

They said to me “We don’t think you’re ready yet, but what if we offer you a multi-year plan and you can come and work with us.” I didn’t believe them but I didn’t see a lot of possibilities in Colombia, I knocked doors everywhere. I stuck to [their] plan, and I was able to apply for a scholarship in 1999.

Jaime has since settled in Sydney, where he now has a family and is advising students of his own. One of them was working in the United Kingdom and connected him with the GROW Colombia initiative, which is directed by Professor Federica Di Palma. He started working with them on programs for academics, but tells me “I realized that something was missing there.

I said OK, I have these ideas. I already had some experiences in Colombia working with communities, I knew a little bit about the history, about the situation, and I said we can do this with these combatants. What’s simple but powerful is we can empower these combatants to know and understand nature, so they can contribute to science in doing inventories of biodiversity but actually using that for ecotourism...they are undertaking in remote areas of Colombia as part of the reincorporation into society.

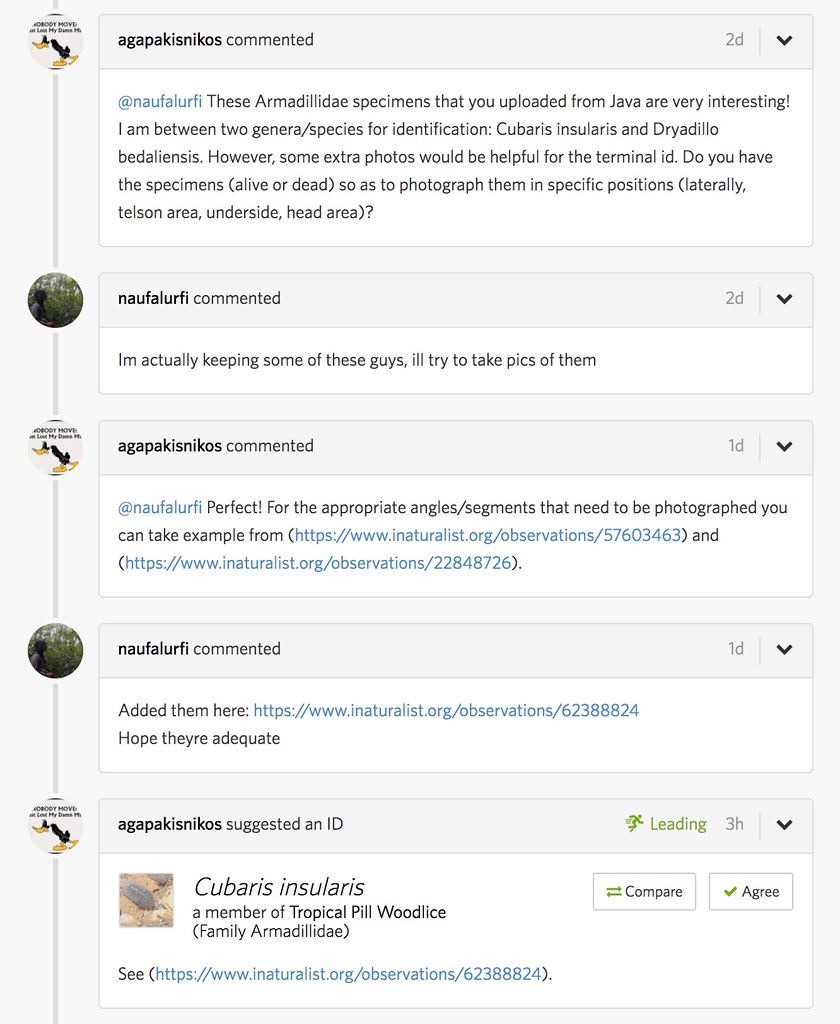

The program, called Peace with Nature*, came together over the period of about eighteen months. Much of this preparation involved building a network of Colombian scientists and researchers who could help, as Jaime wanted the former combatants to build relationships not only with him but with a community of scientists in the country. As they started to design workshops and trainings, they made sure to not only teach standard methods of taking inventories (including using binoculars for wildlife, “which they had [previously] only used to look at enemies [with]”) but to combine that with the former combatants’ deep traditional knowledge of the environment they’d lived in for decades. For example, some former guerrillas have pointed out the differences between two plants that a scientist thought were the same species.

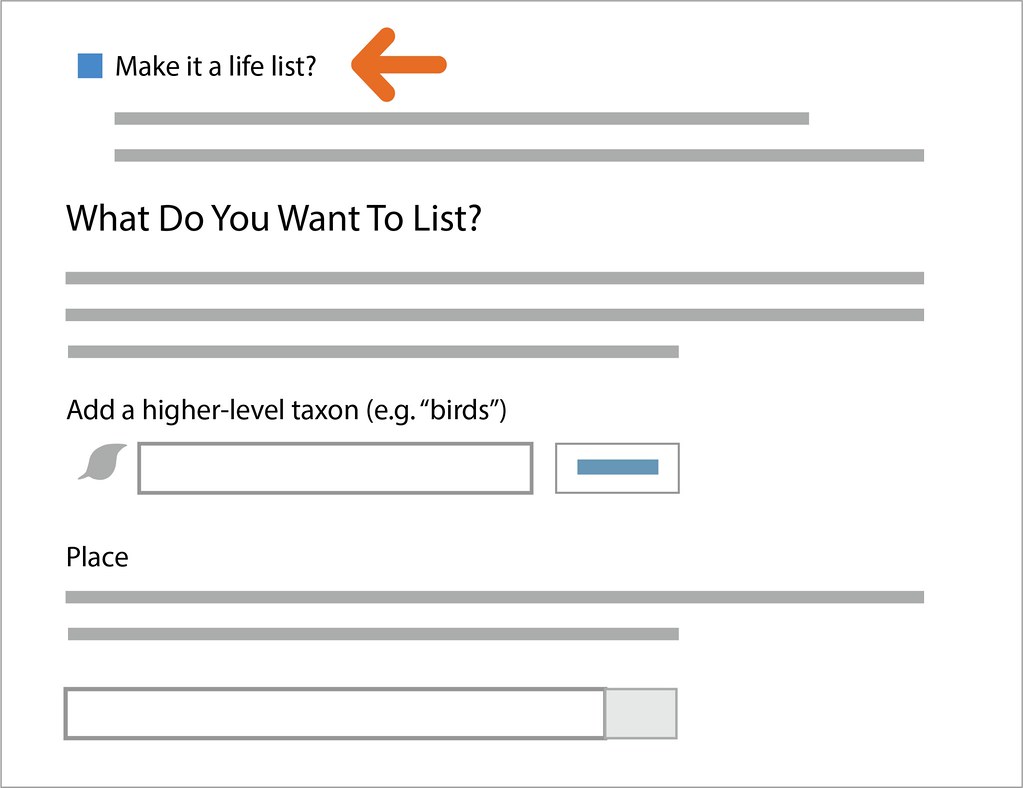

Training also included how-tos for iNaturalist, and iNat’s partner in Colombia, Instituto Humboldt, has been supporting Peace with Nature. Each survey team included a group who were taking photos for iNaturalist, and when they returned to the villages, they uploaded their finds to iNat. Jaime tells me they plan to curate the observations, and that at least one former guerrilla, @ricardosemillas, has really taken to iNat.

These are only the first steps of course, and the group envisions engaging future ecotourists with iNat as well. “[The former guerrillas will] go and...show them the attractions..and the tourists can take pictures so we will be encouraging tourists to increase the participatory inventories through iNaturalist. In that way, tourists become citizen scientists and increase the inventories [in the area],” says Jaime.

While the entire endeavor is clearly close to his heart, Jaime is especially proud of the progress he’s observed when it comes to former enemies bonding over nature. Due to security issues, Colombian military and police - who not too long ago were fighting the guerrillas - accompanied the group and Jaime recalls

I saw an opportunity in particular with the police being close to us, and I said “Hey, come here, you can be involved,” and I have pictures of the guerillas teaching children from schools and the police how to use iNaturalist...In the last workshop we have the first member of the military officially being part of the inventories.

People think sometimes to see the negative aspects of people. My tendency is to see the positive aspects of people. What is positive there that we can use to connect people to a change in behavior that could be transformational for the purpose of your project, in this case conserving nature and reincorporating people into society...iNaturalist is contributing to empower people to do transformational and positive change and to global peace.

- There are a few other articles about this program, check them out here, here, and here.

- And a nice video about the program here. It’s in Spanish and English. As an English speaker, I’ve found that if I turn on captions then, in the gear icon, choose Auto Translate and English, it’s actually pretty understandable. I imagine it works well for other languages too.

* Jaime wants to note that Peace with Nature has been a collaborative project in which he has engaged more than 10 academic, research and government institutions including the Amazonian Scientific Research Institute SINCHI, ECOMUN, ARN, UniAmazonia, and the UN Verification Mission.

Photos courtesy of Jaime Góngora.